How does the saying go? “You can’t paint a Picasso with a paint roller?” I’m sure that’s not how it goes, but the point is, having good tools is the foundation of doing good work. Today, I’m writing about one of the most commonly used tools across academia - the reference management software.

Long story short, I’ve been using Papers 3 for about 2 years now, and I’ve been getting increasingly annoyed by it over the last few months. Naturally, I flipped through the internet to see if there exists a comparison of the more recent tools available to help me make a decision. To my extreme surprise and exasperation, I found none. So I decided to bite the bullet and try all the ones I could get my hands on to see which one I liked more. This took me a good month or so, but hey, now that I did the hard work, you don’t have to.

This post is rather comprehensive, so I’ve collapsed the detailed comments for each app, leaving just the intro and summary. These are aimed at helping you make a decision as quickly as possible, based on your needs. You can find the detailed notes for each by clicking on “Click to expand” in each section, which I highly recommend if you’re considering a particular app based on the feature highlights.

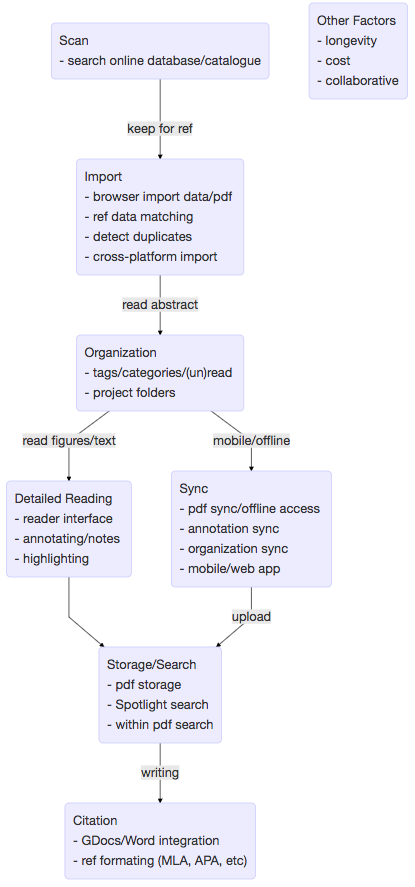

One last thing before we get to the good stuff: my preferences are specific to my literature reading workflow, which might be different from yours. In particular, I do most of my reading electronically (and on a mobile device), and I often receive/find one-off recommendations from the lab or Twitter, which is a pain to manage without disrupting my day. With that in mind, I drew a flowchart of my workflow (programatically generated in Markdown, with mermaid!).

Click to expand workflow flowchart.

Briefly, the steps are: get paper (Scan/Import), file paper (Organization), read paper (Reading/Note-taking), and later, find paper (Storage/Search and Citing), with the additional requirement of syncing (Offline/Sync) between two devices - I do all my writing on my laptop, and ideally, I will be doing all my reading on the iPad. Each software is judged based on those categories, so that if you skip some of those steps in your workflow, hopefully the other sections will still be informative.

If you’re just starting your research career, be it graduate or undergraduate, I hope this guide will inform you on which app you want to use for the next few years based on your needs. And if you’re a seasoned academic that just happens to be displeased with your reference manager, keep on reading.

tl;dr:

Most of these apps are on an equal footing with regards to the core functionalities: importing, filing, reading, and creating citations, though the small features that do differ can make or break it for you. Other than that, it’s a question of whether you prefer a traditional (offline) app or a web app, whether you will read on a mobile device (phone/tablet), and making the trade-off between feature-rich but clunkier, or spartan but lightweight.

- Papers 3 was great, but it’s going downhill fast and you should not buy it.

- ReadCube doesn’t have tagging (wtf) and, while the other necessary features are there, there are some superfluous ones slowing things down. Probably the most complete ecosystem (desktop, web, and mobile app), and may improve with the merged ReadCube-Papers app.

- Zotero is free, open source, and NOT owned by Elsevier. If you need a desktop-only (offline) app that works well with Word, with the potential of useful future add-ons (e.g., Zotfile), this is the one for you.

- Mendeley is not here. Just use Zotero instead.

- F1000Workspace is a free web-app, very functional but a little claustrophobic. It only works online and has great integration with Word and Google Doc. Good pick if you rarely need to read or write offline and don’t mind bad UI design.

- Paperpile is also a web-only app, but is beta testing an iOS app that has full offline functionalities. Lightweight, functional, and pleasantly designed app interface, but only works with Google Doc (for now).

Spoilter alert: I ultimately went with Paperpile, but it was not by any means a decisive victory. This really depends on your own workflow.

Go to: Papers 3 | ReadCube | Zotero | F1000 | Paperpile

Papers 3

Price: $50, one time

I’ve been using Papers 3 for the last 2 years, and I really liked it. I paid 50 bucks for it, so you bet I’m gonna like it. Overall, the desktop (Mac) and iOS apps were great - rich features, automatic syncing over Wifi and Dropbox, and serviceable customer support. But the entire reason for this deep dive on reference management software is that I wanted to switch from Papers, and it’s for two reasons: first, various aspects of the app are getting buggy, ranging from general slowness of the desktop app during searching/accessing pdfs, consistent crashing of the Citation plug-in, and weird sync issues with the iOS app; second, Papers is now merged with ReadCube, and they are to rollout a new ReadCube app soon under a monthly subscription model. Papers 3 users can upgrade at a discount, and the old app will (so they say) be supported indefinitely, but let’s be real here: it’s getting killed. Ultimately, it was a great piece of software that, I felt, focused on the right things. But given the state of the merger, I would not recommend shelling out $50 for it.

Click to expand for details and screenshots.

Scan/Importing (6/10): Scanning for articles in the Mac app itself is easy, and I’ve actually used it a bunch for doing literature searches prior to starting a project. Importing a references from the search interface is just one button-click, but getting the pdf itself can be a pain with paywall journals, as you have to click through multiple pages in this clunky web browser inside the app. You can also just drag and drop pdfs, and reference matching for published articles, for the most part, is very accurate. Duplicate reference detection is automatic, and clearly displayed as a column. The one thing that really annoyed me was that there was no easy way to import a paper while tagging and filing at the same time. I would often read a paper’s abstract online, scan the figures, and decide that it could be a useful reference for the future. From that point, with Papers 3, I would have to download the pdf into the designated watch folder, and open the app to tag or write down my immediate thoughts. Since the app is so bulky, I usually just save that step for later (read: never), except this introduces unnecessary work later because I already know how I want to file this paper at this moment. I hated this so much that I started to append what I would have tagged as the file names when I saved them. I thought this problem was unavoidable until I tried the other apps on this list, which all have Chrome extensions for direct import into library and easy tagging - life-changing. Having a sensible organizational system is great, but its usefulness is directly tied to how easy it is to actually use it.

Organization (9/10): Papers offer a large set of organizational tools, including tags, collections (folders), colors, flag (for importance), and read/unread marker. I used tags to tag permanent properties, like the method used in the paper or the model organism, folders for each of my ongoing projects, colors for denoting the level of detail to which I read the paper (green for abstract, red for full text, etc), and flag for marking really relevant papers that I will probably revisit. I’ve gotten used to these different markers, so it feels natural, though my biggest complaint is probably that there doesn’t seem to be a way to hierarchically organize tags, and finding articles under multiple tags is needlessly difficult (compare to Zotero).

Reading/Note-taking (9/10): Papers offer its own reader, which opens the pdf inside the app. Highlighting and text-box comments are easy to make, and these annotations show up on the righthand side toolbar during reading (reader-view) and preview (library-view). You can also write plaintext notes within the toolbar. It looks like highlights made in Preview are visible in the Papers reader, but the other way around doesn’t always work until the library (and pdfs) are formally exported out of Papers, which show up as external notes in all the other reference management programs. Minor inconvenience.

Mobile/Offline Syncing (5/10): Because the Mac app runs locally, and all pdfs are stored locally, reading offline on the computer is not an issue. In contrast, while the iOS app attempts to mirror the same kind of functionalities on the iPad, it falls short. Theoretically, this is the perfect iPad companion app. Practically, it’s unreasonably buggy and slow, so much so that I actively don’t want to use it. Again, the tool is as great as how often you actually use it. For some reason, syncing changes to <10 pdfs take multiple minutes, especially annotations and tags. I don’t know if it’s because I’m doing it over Wifi, as opposed to over Dropbox, but I suspect it’s because of the virtual disk system Papers sets up to manage and store the pdfs (don’t care enough to dive into, and I don’t quite understand why it needs to be that complicated). To be honest, if there was any prospect of this thing getting better through updates, I would probably happily suffer for a few more months. But as it stands, unlikely.

Storage/Search (4/10): Papers used to have great Spotlight integration, such that both titles and text within the pdf can be searched. For some reason, that functionality is gone. No matter, Papers comes with a tool called Citations, which serves as the citation insertion tool, but also a private Spotlight. It works really well, I almost always find the paper I’m looking for within a few words. Huge caveat here, though: from around 6 months ago, Citation has been crashing 75% of the time when called up via hotkey. I’ve emailed support and they say other customers have been experiencing similar issues, and basically told me to reinstall as a solution. Well, I tried, and it didn’t work, which makes me more skeptical of continued support (though the support staff I interacted with were all very pleasant and tried to be helpful.) Searching within the Papers app, though, gives you the joyful experience of traveling back in time, like if you were using a Win95 PC, especially when searching by author. For some reason, this takes literally forever (I have about 1200 pdfs), to the point that it lags my computer as I type in the author’s name in the search bar. Again, not exactly sure why, but I think it relates to the way Papers implements its virtual file storage architecture. All that complexity is fine if things worked well under the hood, but it doesn’t, so I’m very disappointed about what was otherwise an amazing tool.

Citing (6/10): As I mentioned earlier, Citation is the magic tool that integrates search and citation embedding in one go. Citation integration with Word is fantastic, where inline citations are inserted as citekeys (placeholder tags). Once you’re done writing, it’s a one-button click to convert all the inline refs into whatever format you had declared, and there are plenty of styles available, including all the common ones (APA, IEEE, etc.). It also automatically populates a reference section at the end of the document, in the said format. In contrast, it’s not at all integrated with Google Docs, and the magic formatting doesn’t work there. However, you can paste the full formatted version of any reference directly into a editable text box anywhere, including Google Docs. It’s much less handy for keeping track of the inline citations, as you’d have to manually edit those and manually keep the correspondence between inline citations and formatted reference.

In Summary: It was good while it lasted - Papers was a great tool for the last few years. It seemed like the savior of academic reference management in its earlier days. As it grew over time, however, the software just got more bloated and fragile. Since the merger with ReadCube, it feels like they’ve abandoned the current app and are actively funneling users to the subscription-based service, which constantly reminds me of the intrusive and cluncky web pdf reader adopted by the Nature family journals. Well, if the developers themselves are telling you to use another service, who am I to say otherwise?

Go to: Papers 3 | ReadCube | Zotero | F1000 | Paperpile

ReadCube

Price: $36/year (free with institutional subscription)

I originally wasn’t even going to give ReadCube a try, out of principle, due to its relationship with Nature Publishing Group and the paper rental service model. But then I decided that I should really be comprehensive. So I begrudgingly downloaded it and imported my entire library into it, which was easy, if a little slow. I grabbed the Chrome extension as well, which let’s you import papers directly from a journal html page. There is a desktop app, a web app, and an iOS app, which means preserved functionalities while offline. I poked around both the web and Mac app, the interface design is consistent between the two and pleasing to the eye, with most of the space dedicated to the library view itself. It even has a sidebar that displays the citation history and all papers citing the current one you’ve highlighted. As much as I hated the pdf viewer when it randomly popped up on Nature pages, I actually thought it was really polished in the context of the app. Syncing between the web app and Mac app is automatic and painless, and I have no reason to expect otherwise for the iOS app, though it’s unclear where the pdfs are stored.

It has all the ingredients to be an useful and dependable tool, and surprisingly, I think I would have had a hard time not choosing ReadCube, had it not been for one feature that made me want to banish this thing into oblivion (and hence not write the full review): there are no tags. Okay, that’s not strictly true. You can tag an article, but only as hashtags in the notes area. The hashtags are used to aggregate articles into lists, which is the basic (and only) unit of organization in ReadCube. Hashtags cannot contain space, has no color coding, and all of them are flaccidly listed in the left sidebar with no way of organizing them otherwise. I don’t know what made me more upset: that this app is missing such a simple but key feature, or that it’s a great app in every other dimension. My only other complaint is that it feels a bit clunky and slow at times. This may be due to a combination of the unnecessarily rich visual design for the interface and the nice but superfluous features, like loading the entire citation list in the sidebar.

And so with that, I end my full review of ReadCube: if you don’t use tags or just plain hate organizing your papers in a sensible way, give this a try, it’s pretty good in every other way. By the looks of it, the new (beta) ReadCube-Papers app retained a lot of Papers 3 organizational features, so that might be worth a try when it’s available for the public. Although, it’s more likely than not that it will still be slow and clunky, especially compared to the more light weight apps like Paperpile, or even Zotero.

Zotero

Price: $ 0/ $ 20/ $ 60/ $ 120 (300MB/2GB/6GB/Unlimited Storage)

Zotero, like Papers 3, is a desktop app that primarily runs offline. The functionalities are very similar to Papers, and so is the interface. The main difference here is that 1) it’s (mostly) free, 2) it’s an open source project, and 3) it doesn’t have a companion mobile app. In exchange, however, there are a few very handy tools that make life easy, which I will highlight below. Note that I haven’t used Zotero or the other apps extensively, like I have with Papers. I have, however, imported my entire library into it and spent a few days working with it AS IF I was using it, by going through all the steps in my workflow.

One note about Mendeley: I used Mendeley when I first started graduate school, and it was serviceable. I would say that Zotero is basically a faster (and less evil) version of Mendeley, without a mobile app. If you’re happily using Mendeley, all the power to ya. If you are considering switching to Mendeley, I would give Zotero a try first to see if your needs are met.

Click to expand for details and screenshots.

Scan/Importing (10/10): pdf drag and drop works smoothly, and you can add items by DOI, so it’s very arXiv/bioRxiv friendly. The most convenient add-to-library function, though, is the Chrome extension. Clicking the toolbox on any page will import that reference into your Zotero library, and the transfer between Chrome and the Zotero app itself is seamless. This works for both the html and the pdf page, and it automatically grabs the pdf into your library. Not only that, you can tag the newly added reference in the extension toolbar itself, as well as direct it into the relevant folder, so you don’t need to leave Chrome at all. The only thing it lacks is a confirmation button, as clicking the extension button automatically adds the page you’re on, and I’ve accidentally done it a few times. I looked around, but didn’t find an integrated database scan option, though there is an automatic “import from feed URL option”. Either way, I think the Chrome extension more than makes up for it while using Google Scholar or PubMed. Finally, batch import via .ris files exported from Papers 3 works perfectly, even getting all the tags and notes right.

Organization (10/10): The basic features are all there, very much like Papers. You can tag a reference, as well as assign references into non-exclusive folders for different projects. There are less options than Papers, though. For example, it lacks flag/no flag and star rating. But those can easily be compensated for with a few custom tags. I do really like the fact that you can assign groups of tags to the same color, which makes browsing tags a lot easier. Also, as per standard, main library view offers many columns (author, title, etc.) and you can sort by any. In short, nothing to write home about here, but that’s arguably a good thing because everything just works well and quickly.

Reading/Note-taking (6/10): Zotero does not ship with an in-house pdf viewer, so on a Mac, it’s automatically opened in Preview. I’ve never quite decided whether I like native pdf readers more or embedded pdf readers, so your personal preferences may vary. Aside from aesthetics, the main issue is how well your pdf highlights/comments get parsed as notes, and later, how well it transfers out of the reader app. In this case, Preview keeps the highlights, which are visible in other pdf readers. Extracting annotation from the pdf is not supported by Zotero itself, but there’s a handy open source add-on called [Zotfile][zotfile] that can perform the extraction and turn highlighted words into notes. You can run this operation in a batch fashion, but it is not automatic, so this whole operation is slightly inconvenient. Adding notes is simple enough in the side bar, though you may have to switch windows constantly if your screen can’t fit the pdf and Zotero together. [zotfile]:http://zotfile.com/

Mobile/Offline Syncing (5/10): Since Zotero lives locally on the machine, there’s no syncing necessary if you read on your laptop, and you can use it wherever you are, no Wifi required. My main (and only real) complaint about Zotero, and ultimately the reason I did not go with it, is that it does not have a companion mobile app. There used to be a third party app called Papership that basically did all the file management, but it’s been abandoned as of a few years ago. Zotfile, once again, offers a reasonable but inconvenient solution: if all the pdfs live on Google Drive, it’s able to pull any annotations and updates and sync with the local files. This means you can read the pdfs in your preferred pdf reader app on your tablet, highlight and annotate, and Zotfile will make the transfers. It works, but it’s clunky. You can’t use the functionalities of Zotero while on the iPad, meaning no tagging or categorization, or search, for that matter. Also, Google Drive, for whatever reason, does not allow entire folders to be downloaded offline, so you’ll have to manually “make file available offline” anytime you add new papers. It’s not a huge deal either, but the Drive UI doesn’t really make this an easy job.

Storage/Search (10/10): All pdfs can be stored in a single folder, be it a local one or a synced folder, so file management is painless. If you choose to shell out some money, I think your pdfs are synced with Zotero’s server. Or you can use your free 15Gb from Google. Another feature Zotfile offers is batch renaming of the pdf files based on some arbitrary rule you can define, like author_title_year.pdf. This means relevant search words in the title can be picked up by Spotlight, though whole-text search is less dependable. Search within the app is fast, which should not come as a surprise for a piece of modern technology managing a few thousand pdfs (ahem Papers 3). Anyway, my favorite Zotero feature is the ability to select multiple tags in the toolbar as an “AND” search: when you click on one tag (“oscillation”), all tags except the ones co-tagged to “oscillation” are eliminated, so you can iteratively click on overlapping tags to filter your search. This is an awesome feature and I don’t know why none of the other apps have adopted it, it makes searching so easy when you can’t think of any search words. Granted, you need to have a reasonable tagging system.

Citing (7/10): Zotero lacks a magic genie citation insertion tool that runs in the background like Papers 3, so you can’t search for references unless actively writing inside a Word document. The Microsoft Word add-on is minimalistic but fully functional, though it requires Zotero to be running as well. In any case, all you need here are two buttons: “Insert Inline Citation” and “Format Bibliography”, with some way of controlling the citation style, and Zotero does this fine. When searching for the reference, it takes you into the main app and opens up a sleek search bar similar to Papers. Disappointingly, Zotero does not have Google Doc integration, and its documentation suggests dragging and dropping from the app, though that will of course require manual shuffling when you need to change some references. Alternatively, you’re offered the option of downloading and uploading the GDoc file as a Word doc, or manually insert cite keys when you write and run format once in the end. Any changes made online will have to be taken offline and synced. This mirrors the situation with mobile reading - you can make it work if you want to, but will be a pain in the ass if Google Doc is your main tool.

In Summary: Zotero is an excellent (and free!) tool that I would highly recommend if you mostly read on your computer and write in Microsoft Word. You’re essentially getting the same organization, functionality, and aesthetics out of an open source piece of software as Papers 3 (or Mendeley), except you get to keep your money (or soul). In this day and age, and with Zotero’s sizeable existing user base, it seems that being open source is not at all disadvantageous to continued development. If anything, it takes a smaller community of dedicated users, or even a single individual, to add or improve some functionalities, as was the case with Zotfile. But if you depend heavily on Google Doc for writing, or read primarily on a synced mobile device, then unfortunately it will be difficult to use.

Go to: Papers 3 | ReadCube | Zotero | F1000 | Paperpile

F1000Workspace

Price: Free, $10/month for additional features and storage (free with institutional subscription).

F1000Workspace is the reference manager in the F1000 ecosystem (with F1000Prime and F1000Research), short for Faculty of 1000. I have no idea what that means, or why someone decided they had to use those same words to name the services as well. F1000Workspace is a web-based app, and it’s honestly the quintessential embodiment of what the public thinks of scientists (and engineers): functionally, it really does its job, and that’s that. It has no fluff, it doesn’t care what anyone thinks about how it looks (perhaps to a fault), or what its name is.

Click to expand for details and screenshots.

Scan/Importing (9/10): Importing references is easy: from the web app interface, you can drag and drop local pdfs from your computer or import from various cloud storages. Alternatively, importing batch-wise via a .ris file worked just as well, along with my notes, but tags did not import. It seemed to have a little trouble matching references that were sections from a book, compared to Papers at least. But for all my article pdfs that were indexed in PubMed or otherwise had an easy to access DOI, it worked just fine. Like Zotero and Paperpile, it has a very convenient Chrome extension that allows you to grab references from the journal site you’re currently on, or the pdf link itself. It even offers tagging and filing from the extension, which I love. This means you can read through once, import and organize in one go without ever visiting the web app itself, and forget about it until you need to cite it. Other apps should take note: it’s a small convenience, but would save the user a ton of time over the years if they didn’t have to visit the main app to file and tag. You can also download the offline companion app and set up a to-watch folder on your computer, where pdfs are automatically imported.

Organization (5/10): F1000 has the standard pair of organizational tools: folders and tags (tags can have colors as well). Instead of “Folders”, F1000 calls them “Projects”, which serves the exact same role as far as I can tell. The only difference being that you can file references into a “Shared Project”, which makes collaboration easier than exporting a folder of references and emailing it, though I’m not sure if the recipient also needs to be registered with F1000. The downside to the free version is that you can only have 3 projects at a time, which is a pretty small number, but this limit is bypassed with institutional or paid subscription.

One thing I really don’t like is the app interface itself in Library view. There is a ton of dead space you can’t control, and with a reasonably sized screen, the actual reference list panel is tiny and you’re limited to looking at ~10 references at a single time. What’s worse is that the fields are truncated to fit more of them. Sure, it’s not like you will actually be searching through references by scrolling all the time, but any keyword that returns 10+ results will be a pain to scroll through. Oh yeah, and scrolling does not auto-populate the next set of references, so you need to click the “next page” button. This certainly makes me feel a little claustrophobic, and I fear that some references will be buried forever because I will never click through 20 pages to explore refs I might have missed while writing.

Reading/Note-taking (10/10): F1000 offers a web pdf reader app that is packed with note-taking features. You can add highlights, sticky notes, and even notes to your highlights. From your library, you can also directly access the article html site, and even make notes and highlights on there that syncs to the pdf itself when the little ‘F’ pops up. That’s pretty cool, and is great for that first-time read through. Bonus if you like to read the html version. Overall, I think this should be the gold standard of reading and filing articles on the web.

Mobile/Offline Syncing (2/10): The biggest weakness with F1000, as you might expect, is its (in)ability to function offline. If you’re not connected to the web, the web app obviously will not work. This means you cannot offline search, read, file or even cite, because you cannot access the database. F1000 offers one work around: while you’re still online, you can add references to a “reading list”, which the offline companion app can access and open the associated pdf. Key caveat here is that you every time you quit the app, you have to sign in the next time you open it, which you cannot do offline. So overall, this is rather pointless, especially if you save your pdfs locally as well. F1000 has an iOS and Android app that looks identical to the web app and pdf reader, and poetically, it suffers from the same offline issue. There is no way to locally save pdfs on the iPad, and if you’re offline, the app is basically a dud. In other words, the mobile app turns your tablet into a screen that you can take with you but only when there’s Wifi. The upside is that syncing works quickly and flawlessly. I suppose this is not unexpected if the app basically opens a tablet version of the web app. In the end, I like writing and reading on the bus/plane/subway, so offline access is crucial for me, especially on mobile. But depending on your needs, this might not be a huge issue.

Storage/Search (8/10): Since F1000 exists as a web app, you can only search in the browser, i.e., no magic tool. Nevertheless, keyword matching is satisfactory, as it searches in title, abstracts, and highlighted pdf text/annotations. The downside, like I mentioned above, is that you cannot search offline, and any search result that returns more than 20 reference will be painful to work through, especially if you don’t know these references by the first 5 words of the title already. The upside to F1000 is that tag searching works conjunctively, like in Zotero, so clicking on multiple tags will return the intersection. I really love this feature, since my tag system includes multiple taxonomies. So it will be incredibly easy to find studies that look at, for example, human + oscillation + ECoG + attention, based on my own tags, instead of relying on text search. Storage-wise, all the pdfs seem to be magically stashed somewhere, perhaps on an F1000 server. Paid (and institutional) subscriptions offer unlimited storage, so this will never be a problem. Batch exporting pdfs is straightforward as well so no need to worry about losing all your references into the abyss.

Citing (10/10): F1000 actually offers the most comprehensive integration with both Word and Google Docs. The Word add-on includes a full suite of tools, including the ability to directly submit your manuscript to F1000, though I cannot imagine that was by popular request. The standard ones, however, work well, and you can actually search by tags, projects, and search Google Scholar and PubMed from the toolbar in addition to your F1000 library. Since it doesn’t work at all offline, it offers the ability to suggest references for manually inserted citekeys, so that you can still write offline uninterrupted, and add in the references when you’re online again. The Google Doc extension works just as well, though my one small complaint is that the citation tool (on both platforms) is a bit slow, as it seems to load the entire library database when it’s first opened. That is a small price to pay for both GDoc and Word compatibility.

In Summary: F1000 is kinda like the web app version of Zotero. It’s a great tool, and aside from offline access, it prioritizes all the key features (importing, filing, reading) and it does them well. Equally important, it doesn’t offer useless features, well, except for aspects of the Word plug-in. The full features may be accessible to you for free if you work at a North American or European institution, and it even has both Word and GDoc integration. If you read and do most of your work while online, and don’t mind the awful interface too much, I would highly recommend trying this tool. But if you need any offline access at all, say, while commuting or during field work in remote places, then you’re out of luck.

Go to: Papers 3 | ReadCube | Zotero | F1000 | Paperpile

Paperpile

Price: $36/year

The best way to describe Paperpile is that it’s like the minimalist hipster child of Papers 3 and F1000Workspace. It’s a web-only app with a sleek interface that is, in my opinion, a lot more pleasing to the eye. The strength (and limitation) of Paperpile is that it links to (and is locked to) a Google account and takes advantage of your Drive space and organization. You’re limited to online use on the computer, but the iOS app is fully functional offline. This is ultimately the one I ended up going with, as it fits my workflow well and I really like the minimalist design of both the web and iOS app.

Click to expand for details and screenshots.

Scan/Importing (9/10): Drag and drop pdf importing, .ris (and other reference file format) batch importing, and direct DOI importing are all available and work well. It also has a Chrome extension that snags the reference and its associated pdf from the journal html website. The weird thing is that the extension cannot import when you’re on the pdf page instead of the html page - mildly disappointing. Also, I wish the Chrome extension supported filing and tagging on the spot, instead of having to do it from the web app (though dev forum suggests this is in the works). One cool thing is that it is totally integrated into Google Scholar (and other databases, like JStor), so that you can grab references directly from search results.

Organization (10/10): Paperpile offers tags, folders, and star labeling, which can all be accessed from the left sidebar. Tags can be colored for easier visualization, and folders can have an infinitely deep subfolder structure, which I believe is unique to Paperpile. Shared folders can also be made, so it’s designed with collaboration in mind. As for the app itself, it displays an even smaller number of references than F1000 at full window size (6.5 on my screen). But for some reason, I don’t mind it so much. I think it’s because the list view actually takes up more than half the screen, and all relevant information for the displayed articles are actually there, with full bolded titles. On top of that, scrolling is smooth and automatically populated as you reach the bottom, so it’s a much more pleasant experience. Another nice touch is the gmail-style keyboard shortcuts, including Shift-Arrow to select multiple, and Cmd-C/B/K to copy as full reference or citekey. I wonder how many people made it to this point without rolling their eyes and saying “just use latex”.

Reading/Note-taking (10/10): Paperpile’s old web pdf viewer was atrocious. It basically used the native Chrome pdf viewer, which means no highlighting, no annotations, no nothing. Recently, they’ve rolled out their standalone pdf viewer app called “MetaPDF”, which can be selected as the default reader opened by Paperpile. This is the polar opposite of that old pdf viewer. First of all, and most importantly, it’s pretty. Second of all, you can make highlights, notes, and notes for your highlights. You can even draw shapes and stuff, and all these are embedded into the pdf itself and readable in other viewers. This very much rivals F1000’s online pdf viewer, and pretty much all the embedded pdf viewers of the offline apps on this list. Taking longer notes can be done from Paperpile’s library view itself, but not from within the pdf viewer.

Mobile/Offline Syncing (7/10): Being a web app, Paperpile suffers the same fate as F1000 when you’re offline, since you can’t even access the URL. Again, this means no reading, writing, or filing. However, there is a beta version of the iOS app that you can request access for and download via TestFlight. The app is fully functional offline, meaning you can tag and annotate, and changes will be synced once you’re back online, as long as the pdfs are also downloaded onto the iPad beforehand. In my experience, the syncing has been painless, both for tags and annotations made in the pdf. There’s no batch download yet, but at least the download button for each reference is huge. This capability somewhat offsets the lack of offline functionality for the web app, as personally I’m much more likely to read offline on my iPad than on my computer. Still, if you must use it offline on your computer, then look elsewhere. They did not pay me for this post. Sponsorship please?

Storage/Search (7/10): Paperpile is linked to your Google account, and it uses Google Drive storage space to store the pdfs. This is potentially very nice or very limiting, depending on how capped your Drive space is, though my library of 1500 pdfs only takes up about 3Gbs. The convenient thing about having the pdfs on Drive is that they can be synced to your computer as a Drive folder, so the pdfs can be accessed offline. Although, you need to be a bit careful about housekeeping since the developers recommend making changes to your library strictly through the Paperpile app, and not by moving files around in the Drive folder. Overall, this is an elegant shortcut, and it’s likely that Google Drive will be around for a while still. But depending on your stance on privacy, having yet another aspect of your life tied to Google may be unideal. Search bar searching within the app is satisfactory, and is limited to keyword matches in the title, abstract, authors, and notes. This is a step below the full text and within-pdf annotation search features of F1000 and Papers 3.

Citing (6/10): Currently, Paperpile only has citation integration for Google Doc. It’s fast, accurate, and has a nice feature for searching directly online while inserting citations. If your “friend” is someone who writes down off-the-cuff claims and finds references later to back them up, this is an invaluable addition. On the other hand, it currently does not have a citation tool for Word, so you’re stuck with copying refs in the main web app and pasting them manually, or uploading your Word document and converting it to a Google Doc and adding all your references afterwards. Fear not, however, it looks like a Word plug-in has been in the works and will be pushed out very soon, as well as offline usage, so it may be worth to stay tuned.

In Summary: Of the apps I reviewed, Paperpile seems to have the biggest potential to improve. The development team is aware and routinely engages with feature requests on the user forum, and my own experience with the in-app chat has been excellent as well. I sent a message to request the beta iOS app, and someone replied within 24 hours and also extended my trial by two weeks to make sure I had plenty of time to test with the app in my workflow. It really is nice to have that dependable human support in your products. Looking through the forum, my hope is that the crucial features (e.g., Word plug-in, better Chrome extension, offline capabilities) will be rolled out in 6-12 months. But as of now, Paperpile is a great fit for anyone that already works online and within the Google ecosystem, and enjoys the UI/UX it offers.

Go to: Papers 3 | ReadCube | Zotero | F1000 | Paperpile

Bonus: code for generating the flowchart in mermaid-compatible editors.

```mermaid

graph TD;

search("Scan

<br>- search online database/catalogue

")

import("Import

<br>- browser import data/pdf

<br>- ref data matching

<br>- detect duplicates

<br>- cross-platform import

")

read("Detailed Reading

<br>- reader interface

<br>- annotating/notes

<br>- highlighting

")

file("Organization

<br>- tags/categories/(un)read

<br>- project folders

")

storage("Storage/Search

<br>- pdf storage

<br>- Spotlight search

<br>- within pdf search

")

cite("Citation

<br>- GDocs/Word integration

<br>- ref formating (MLA, APA, etc)

")

sync("Sync

<br>- pdf sync/offline access

<br>- annotation sync

<br>- organization sync

<br>- mobile/web app

")

other("Other Factors

<br>- longevity

<br>- cost

<br>- collaborative

")

search--keep for ref-->import

import--read abstract-->file

file--read figures/text-->read

read-->storage

storage--writing-->cite

file--mobile/offline-->sync

sync--upload-->storage

```

You made it to the end! Now pick your starter Pokemon and go forth into the wild world of reading lots of papers you will never remember!