I didn’t forget about this. My laptop bricked back in February and somehow the one meaningful thing I lost was this uncommitted draft. The thought of re-writing it was dreadful, so I didn’t. Then life happened, and all of a sudden it’s August. Tale old as time itself.

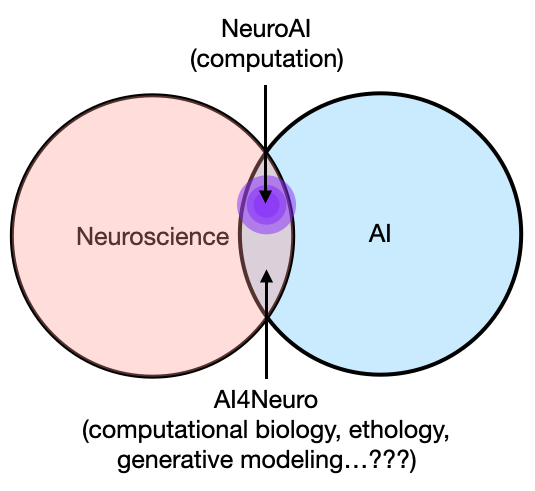

A brief recap: what’s the difference between NeuroAI and AI4Neuro? In the previous post, I used “computational neuroscience” as an analogy to illustrate the difference about developing and using computations for neuroscience vs. understanding computations in neural systems, and that while the two are both valuable perspectives, methodologies, and branches of neuroscience, the latter seems more like an unified entity, and is what is predominantly known as “computational neuroscience” (for example, at COSYNE and CCN).

It took me some time to understand this, and it makes a lot of sense in hindsight. But it was certainly very confusing and frustrating for a while, when it felt like somebody (me) working on developing computational methods for analyzing neural signals—but not prescribing to a specific computational view of the brain—was totally out of place. The correct response, in some sense, should have been “computational biology”.

A few more spins around the sun, I’m still doing neuroscience, but now with “AI”. Apparently I caught it at a good time, overlapping with the surging interest in NeuroAI sweeping across the world. Naturally I wondered, “Am I doing NeuroAI?”

For today’s post, instead of telling you what I think NeuroAI is, I try to find out what it actually is, empirically, by reading what Google has to say.

For starters, I sort of assumed NeuroAI was, well, the intersection of neuroscience and AI. I think that’s pretty reasonable? But I had a budding suspicion for a while now that my presumptive definition was naively broad. Once I started digging, I actually felt pretty stupid for not realizing it sooner, because it’s usually plainly stated within the first one or two sentences, and in a totally non-controversial way.

tl;dr: Concisely stated, my reading is that the key part of NeuroAI—Neural and Artificial Intelligence—is squarely centered on Intelligence. In other words, Artificial Intelligence here is not a compound word as it’s often used now to describe your favorite text-to-image model, but that Artificial should be more lumped with Neural, as in, (Neural+Artificial) Intelligence. It would be equally valid to have called it Artificial and Neural Intelligence, or even more broadly, Artificial and Biological Intelligence (as some do). I would have personally preferred this name, but maybe this reminds us too much of Cybernetics and communism in the 60s.

Some of the references below do specifically mention “the intersection of neuroscience and AI”, and while that’s technically true, you will see in a bit that it’s a rather specific subset of the intersection, centered on—you guessed it—computation.

After the survey, I will explicitly spell out the missing parts, i.e., what NeuroAI doesn’t seem to encompass. I have no other ideas for what to call “the rest of this stuff” except AI4Neuro, and that will be the meat of our next and final installment of this series (coming in March 2025). Finally, I will end with some optional reading about “computation” and our bias for cognitivism, intelligence, and “representations”.

I will again leave the disclaimer here that these are just my opinions. I’m not telling anybody what they should do or put things into boxes when there originally was none. I certainly don’t want to discourage anyone from thinking about computations in the brain. I think (a lot) about this as well—I just don’t know what computation means anymore, and never knew from the beginning what “intelligence” was in a way that doesn’t involve folk psychology explanations.

This blog post summarizes the process of educating myself and sorting through my thoughts, in part to try to figure out what it is that I do. Hopefully by the end of this you will have a better idea of what NeuroAI is as well, and importantly, what alternatives—aside from computation and intelligence—there could be for the role of AI in neuroscience. Part of me just want to shout into the void, where the hell are all the people that want to do neuroscience and AI without prescribing to the ideas of computations and intelligence??? (Or maybe that’s more Part III.)

What is NeuroAI? Our survey results indicate that…

I here employ the very scientific method of Googling “NeuroAI” and clicking on the first things that pop up. To be even more scientific, I went past the first page of results, and also tried different variations of the search term. I will simply provide the data here in the form of relevant quotes, with some minimal commentary, and trying not to misrepresent anything by removing the context of the surrounding sentences. To be clear, I did not cherry-pick for or against certain definitions, but included everything where I considered it to be a relevant statement.

- And where else to start than from this perhaps definitive Perspective article from 2023 titled, “Catalyzing next-generation Artificial Intelligence through NeuroAI”? It’s a nice read. I especially enjoy when such papers come with a historical perspective. A big part of the paper makes the argument that “next-generation” AI will need sensorimotor embodiment, something that is a god-given for animals in the world that engage their environments, behave flexibly, and compute efficiently, but tremendously difficult for human-engineered AI systems. We might come back to the embodiment part, which I think is actually the main point of the paper (arguing against the “platonic computation” / brain in a vat), at the end of the post. For now, here are some very authoritative quotes (all emphasis below are mine):

“The emerging field of NeuroAI, at the intersection of neuroscience and AI, is based on the premise that a better understanding of neural computation will reveal fundamental ingredients of intelligence and catalyze the next revolution in AI.”

“[…] the current AI revolution were planted decades ago, mainly by researchers attempting to understand how brains compute. […] Neural circuits compute effectively despite the presence of unreliable or “noisy” components.”

- Related to this article, a Cosyne panel on NeuroAI took place in 2024, which was reported on in this Nature Machine Intelligence Editorial, “The new NeuroAI”. The article only scratches the surface, and seems to place its emphasis on that 1) NeuroAI is an (re-)emerging field, and 2) people disagree about how much neuroscience really contributed to AI. It does have a nice historical reference, and maybe a diss on scaling and engineering?

“The effects of neuroscience on artificial intelligence (AI), and the mutual influence of the two fields, have been discussed and debated in the past few decades. Not long after the seminal workshop at Dartmouth College in 1956, which launched the field of AI, artificial neural networks called perceptrons were introduced by Rosenblatt […] However, as AI research has evolved at a fast pace, progress over recent years has stirred a divergence from this original neuroscience inspiration. The pursuit of more powerful artificial neural systems in leading AI research labs, particularly those affiliated with tech companies, is currently focussed on engineering. This pursuit emphasizes further scaling up of complex architectures such as transformers, rather than integrating insights from neuroscience.”

- Staying on the academic paper track, finally, a 2017 Perspective article in Neuron, “Neuroscience-Inspired Artificial Intelligence” (and the associated DeepMind press release, “AI and Neuroscience: A virtuous circle”), which perhaps reinvigorated the “new NeuroAI” of recent years:

“In this article, we argue that better understanding biological brains could play a vital role in building intelligent machines […] By focusing on the computational and algorithmic levels, we gain transferrable insights into general mechanisms of brain function, while leaving room to accommodate the distinctive opportunities and challenges that arise when building intelligent machines in silico.”

(Note the statement that an explicit “focus on computational and algorithmic levels” is a choice.)

- No direct quotes, but be sure to check out Patrick Mineault’s NeuroAI archive (news, views, and blog posts) and NeurIPS 2023 NeuroAI collection for a great overview of what NeuroAI looks like today.

Moving on from academic publications, here is a compilation of quotes from some institutions, organizations, conferences and workshops:

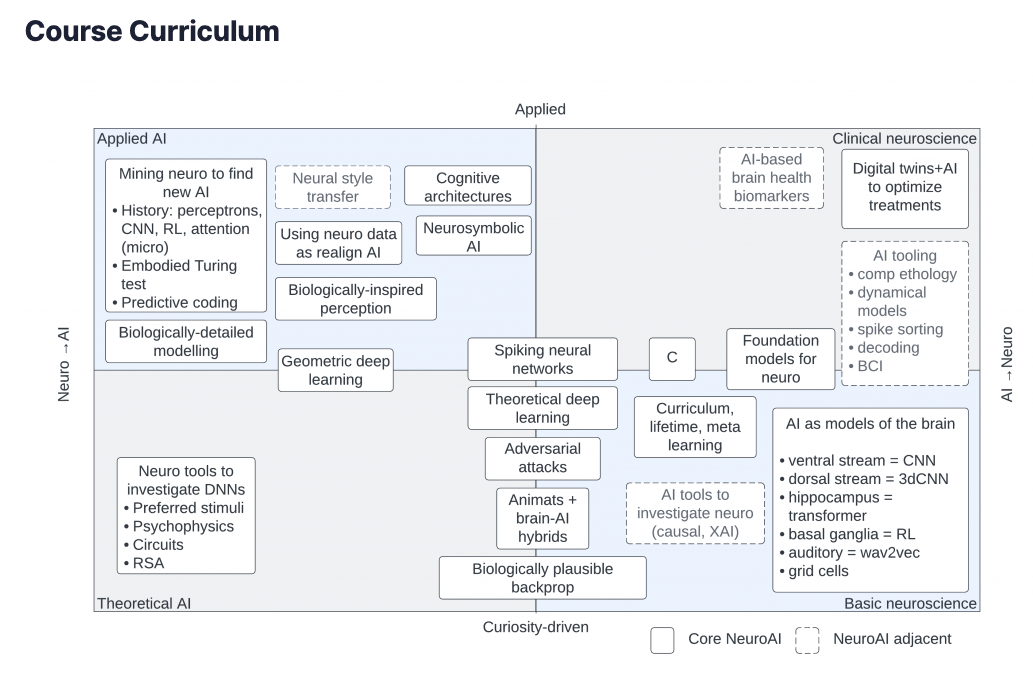

- Neuromatch NeuroAI Course, note especially the delineation of “Core NeuroAI” vs. “NeuroAI adjacent” in the course curriculum diagram (fantastic teaching tool):

“What are common principles of natural and artificial intelligence? The core challenge of intelligence is generalization. Neuroscience, cognitive science, and AI are all questing for principles that help generalization. […] We aim to present current understanding of how these issues arise in both natural and artificial intelligence, comparing how these system features affect representations, computations, and learning.”

- Accepted NeurIPS 2024 NeuroAI workshop:

“This momentum paves the way for exploring the intersections of artificial and natural intelligence – NeuroAI – which promises to unlock novel insights into biological neuronal function and drive the development of computationally less intensive artificial systems trained using small-data regimes.” Key research areas include but are not limited to: Neuro-inspired Computations, Explanable AI in Neuroscience, Self-supervised Systems in NeuroAI, Neuro-inspired reasoning and decision-making, and Cognitive functions in AI.

- Paul Middlebrooks (of Brain Inspired podcast) offers a course on Neuro-AI titled, “Neuro-AI: The Quest To Explain Intelligence”, and under the Neuro-AI module:

“Modern and historical examples of Neuro-AI models that leverage knowlege in the neurosciences, artificial intelligence, and modern analyses, to help explain our own intelligence. The more we can take advantage of how neuroscience and AI can inform each other, the better we’ll be able to understand and build intelligence.”

- Norwegian Artificial Intelligence Research Consortium (NORA), Special Interest Group on NeuroAI:

“The main promise of NeuroAI is that by understanding how the brain and biological neural networks compute, it will be possible to identify the key components of human intelligence to drive the development of a more energy-efficient and flexible artificial intelligence (AI) that will match, or perhaps even surpass, human intelligence.”

(Overlapping in personnel but not sure if related, a NeuroAI workshop on a fucking yacht along the Norwegian coastline. I definitely do NeuroAI now, even if that means I have to do a whole day on Representations.)

- Princeton Neuroscience Institute, NeuroAI and Intelligent Systems Area:

“Recent, dramatic advances in machine learning and AI, such as large language models and deep and recurrent neural networks, have opened the door to powerful new interdisciplinary collaborations between neuroscience and computer science, aimed at unlocking the basis of biological and artificial intelligence. Despite the power of current AI models, we are finding they are not as powerful as the brain in terms of efficiency and learning; neuroscience can inform and inspire better AI architecture.”

- NeuroAI Montreal Workshop 2023 at MILA:

“With remarkable advancements in AI, the impact of biologically-inspired computation on shaping artificial systems is undergoing a transformative shift. While deep learning and other optimization schemes have facilitated remarkable and efficient machine learning, notable gaps between AI and biological intelligence still persist. Conversely, the emergent properties of new AI systems present opportunities to explore the interconnections between computational systems and higher-order cognitive abilities.”

- University of Amsterdam Neuro-AI Summer School:

“The 2024 ABC Summer School “Neuro-AI: Harnessing AI to understand computation in mind and brain” will provide selected students the opportunity to take a deep dive into the promising interplay between cognitive neuroscience and artificial intelligence. […] The past decade has seen an increasing convergence between artificial intelligence and cognitive (neuro)science. Artificial intelligence offers tools to researchers, but has also yielded insights and novel theories about the nature of intelligence and cognition. Similarly, neuroscience and cognitive sciences have also informed and inspired progress in machine cognition.”

- University of Oregon, Center for Computational Neuroscience and AI (NeuroAI Center):

“The NeuroAI Center serves as a nexus for research on computational aspects of neuroscience and applications of Artificial Intelligence to neural circuits and cognition. […] A primary mission of the NeuroAI Center is training the next generation of neuroscientists to crack the neural code through our Interdepartmental Computational Neuroscience Program, a vibrant Seminar Series and our Workshop series in which local or visiting researchers lead hands-on tutorials applying cutting-edge methods from machine learning to neuroscience research.”

(I’m gonna file “the neural code” under Representation.)

- UCL NeuroAI Research Area:

“Crucially, AI shares a common lineage with neuroscience and fundamentally machine learning and the brain employ similar computations to process and compress information […] Equally, AI tools provide a means to discover, segment, and track distinct neural and behavioural states - yielding more efficient experiments and accelerating the pace of discovery. In turn, this understanding feeds back into the design of more effective AI architectures and models.”

(Huge claim on the “similar”, but nevertheles one of the more prominent (and only) places to explicitly mention AI as a tool for understanding neural and behavioral states, orthogonal to it being a model of computation. Respects to the Gatsby Unit.)

- Similarly, CNRS/Toulouse Brain and Cognition Research Center (CerCo), NeuroAI team:

“Our new team embodies the cross-pollination between Neuroscience and Artificial Intelligence (AI). We […] employ state-of-the-art AI methods to effectively address outstanding neuroscience questions. For example deep learning tools are used to find patterns in vast amounts of fMRI and EEG data, and to relate them to stimuli, cognition, behavior and well being. […] and use our knowledge of the brain to design improved AI algorithms and artificial neural network architectures, for example by incorporating spikes, feedback, oscillations, or more human-like representations.”

To summarize…

I think it’s pretty clear what the takeaway is based on the data.

Aside from the last two examples, all references to NeuroAI link it—exclusively—to computations underlying intelligence and cognition in artificial and biological systems. More specifically, the idea is that AI may serve as an in silico model and testbed for the computations underlying our own intelligent behaviors, while understanding neural or biological computations could inspire better artificial computing algorithms and machines. I don’t think this is so controversial of an idea, or at least whether it bares fruit is an empirical question worth pursuing.

To be more explicit: the actual point of this whole exercise is digging for the corollary, which is rarely if ever actually stated, but it’s not hard to read between the lines: neuroscience plus AI, but without considering mechanisms of intelligence and computation, is not NeuroAI—even if the rest of the stuff encompasses most of the intersection.

Then, what’s the rest?

So what happens if you’re interested in both neuroscience and AI, but aren’t working on the shared computational processes between the brain and artificial neural networks, or simply don’t prescribe to the idea of computations in the brain? For the latter, go to the next section.

As for the former, you might wonder, “what can you do in neuroscience and AI and not think about computations?”

Well, think BCI, neural data analysis methods, generative modeling, inference for mechanistic models, pose-tracking and computational ethology, and much more. Basically, “NeuroAI-adjacent”.

“But who cares about what the brain does besides computations, representation, and intelligence?”

Actually most of neuroscience (aka SFN) is allergic to those terms, instead preferring plain, old biology and physiology.

“But why do we need a new hashtag for all the other stuff?”

Funding. Maybe group morale?

Okay more seriously, why go through all this effort just to point out that a bunch of stuff people already do don’t all neatly fit under one umbrella? Why not just call it “machine learning for neuroscience” or something?

Personal conjecture: I think the “computations for neuroscience” segment of computational neuroscience didn’t really take off because it’s so broad that it’s impossible to coalesce, especially in the 21st century where almost everything you do in science involves some kind of computer. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t shared goals and problems across those sub-areas which might benefit from talking to each other, even if it’s about boring ass topics like data management and computational reproducibility (you know, not that there’s a crisis or anything).

For a similar reason, I think it would be beneficial to have a concerted effort in identifying the common opportunities and roadblocks, on both the AI front and the neuroscience front. Things like model robustness and reproducibility, strategies for accounting for heterogeneous and correlated training data, simulation efficiency in software and hardware, etc. These issues plague spiking BCI people just as much as they bother fMRI people, even if they use different-looking ML models for very different scientific questions. But such concerted efforts don’t just happen by itself because a bunch of people are applying AI to neuroscience problems, they happen because people identify with each other, and more importantly, with how “AI” makes their lives fucking painful. The computations and representations in brains and AI will change next month, but the tooling and their problems are here to stay. Luckily, as all-encompassing as it seems, AI and ML is only a very small subset of what you can do on a computer, so there is hope for a united AI4Neuro.

So what are some of these common problems and benefits of using AI across different areas of neuroscience? That’s for Part 3. (Spoiler alert: I don’t know.)

Optional reading: a comment on computation and representation

The purpose of this series of posts is a constructive argument for AI4Neuroscience. But here is a deconstructive (or destructive?) argument against computation (hence optional). I’m by no means the first person to write about this, (e.g., see here). Nevertheless, reading is less cathartic than writing, even if it reveals my ignorance, so consider this more of a…diatribe.

People say that if you do your PhD in something, you realize that nothing on that topic is real and that we actually don’t know anything about that something. I think this is true. The first (and last) thing you learn in Cognitive Science (at least at UCSD) is that we don’t know (or agree on) what cognition is, much less “intelligence”. This fundamentally shaped (or biased) how I think about “computation” in the context of neuroscience and cognition. I don’t want to spend too much time on this, because my current gripe is not really with NeuroAI’s focus on intelligence-as-computation, but rather the lack of other interesting development and application of AI in neuroscience, as we will see later. Also, people much more qualified than me have had detailed and pointed commentaries on this topic. For example, van Rooij et al. had this banger of a sentence in the abstract:

When we think these systems capture something deep about ourselves and our thinking, we induce distorted and impoverished images of ourselves and our cognition. In other words, AI in current practice is deteriorating our theoretical understanding of cognition rather than advancing and enhancing it.

I think this might be worded a bit too strongly, but I don’t fundamentally disagree, though I would replace deteriorating with limiting, and ...AI in current practice... with ...our obsession with computing devices since the conception of the field.... Lest we forget the days when we thought the brain computes via symbolic programs and spatiotemporal filters.

I’m pretty sure I’ve seen this invoked somewhere, possibly Twitter, but if it hasn’t been credited to anyone yet, then I claim this theorem:

“Any state-of-the-art computing device / algorithm is, for some time, how the brain works.”

Is this unproductive? Not necessarily, but if you subscribe to this paradigm, then you probably shouldn’t spend too much time on neuroscience, because you’ll always be lagging behind everyone else, searching for these equivalences rather than inventing new ones. Instead, do machine learning (or math).

Anyway, aside from the general critiques of the dominant notion of cognition, e.g., based on perspectives like embodiment (i.e., cognition is not independent of your bodily limitations) and behavior through evolution (another absolute banger), my one specific issue here is actually rather technical, and it hinges on the notion of representation:

Computation, defined as transformations between input and output signals, is not an unreasonable conceptual model for what the brain needs to do, functionally speaking. However, since (as far as we know) these transmissions and transformations have to operate on physical signals (so, telepathy excluded), the crucial part of computation is that there is recoverable information encoded. Specifically, the operations on the physical stand-in, be it analog (continuous voltage) or digital (0 or 5V) signal, translate to the intended transformations on the representation or “information” we actually care about.

Obviously, in systems we design, whether it’s digital or analog filters, the software in your Roomba, or AI systems, we know the underlying representations because we specified them (but more on that last one in a second). What I mean is that every symbol, letter, and byte maps to something, simply because we enforced this mapping. To be a bit more academic, they are externally grounded to something, and by our design.

However, in systems we didn’t design, like the brain, we have no prior on what is, or even what should be, represented, nor what that representation looks like. So we have to infer or reconstruct it, which is apparently really fucking difficult (though it appears to be difficult to reconstruct even in systems we did design). I mean that’s basically what a significant portion of neuroscience is up to.

As far as I know, the one and only paradigm we have for the last 60 years is to search for neural correlates of induced or measurable stimulus and behavior, and assume that coinciding neural activity is the representation thereof. Sometimes it’s referred to as the “neural code”, and we can argue about whether the code is implemented via firing rate or spike timing, or maybe it’s done by the astrocytes. We can also refine the criterion with which we judge the validity of the representation, like response reliability, signal-to-noise ratio over ambient activity, or predictability with sophisticated decoding algorithms. But we basically assume this representation exists, that we can find it, and furthermore, that it’s stationary (up to context-dependent modulations, which is just another thing to represent and compute on), like in our software.

But is this actually true? No, of course not. I don’t mean it’s not true in the sense that it’s been empirically falsified (quite the opposite, we seem to always find it…), but in the sense that “computing on representations” is just one of many conceptual models of what the brain does. What is this specific conceptual model based on? As many of the references above have alluded to, I guess it’s a consequence of many things converging in the early days of neuroscience, cognitive science, cognitive psychology, and artificial intelligence, but basically, the conceptual model is inspired by the computers and computing algorithms we made. It always has been and always will be: Computation first, biology second.

What’s wrong with this endeavour? Nothing, really, save for the fact that we’re conceptually limited by what exists now, and our collective imagination, which naturally gravitates towards things we intuitively know, understand, and/or can create. I think this is what it means for “computing devices to limit our theoretical understanding of cognition”: we take a very useful but limited thing we made and use that as our template of what the brain does. The computer has well-defined representations on which it performs computations, and so must our brain.

Furthering the cause, these algorithms and computing machines became at some point the best tools we have for analyzing and understanding the signals we measure from our brains, whether that’s single neurons, extracellular field potentials, or now, massively parallel recordings from neural populations. I think neuroscience (specifically, cognitive neuroscience, and now, NeuroAI) is almost unique as a branch of science in that the analyses we use for understanding the measurements are the theoretical models of the thing itself. I struggle to think of another field in the physical sciences where the methodology is not decoupled from the theoretical or mechanistic account of the phenomenon itself. Therefore, I actually have an addendum to the first theorem:

“Any state-of-the-art algorithm for analyzing brain signals is, for some time, how the brain works.”

We are pushing towards a computational theory of the brain because the tools we have, be it filters or AI, is a model of computation, not of physics, and thus, the territory becomes the map. Computation and algorithms are the levels of analysis we chose, of which we build corresponding theories of brain on, which might then improve the computing devices we can build—there is something beautifully self-consistent and circular about that.

Is there a way to get better? I think so. One possibility is to acknowledge and embrace the unexpected complexities of both biological and artificial systems, which is quite relieving since we sort of just need to continue doing what we do but incrementally improve on our current conceptualization. With current AI systems growing more complex, we still know the representation at the input layer because we encoded them to be pixels or word-embedding vectors or whatever, but we quickly lose track of that representation the deeper it traverses through the system, both relative to the original representational space and relative to something that we can perceive and intuitively make sense of. In parallel, we are acknowledging that neural representations are maybe also not as stable (as the trial-mean), though what causes their changes could either be long-context we don’t have access to experimentally, or perhaps something fundamental to the biology (see recent discussions on representational drift). The downside to this is that, on top of the brain itself, we now don’t fully understand the models either, which requires research areas like explainable AI and mechanistic interpretability (though you could reason that’s fine since we really still don’t “understand” Navier-Stokes).

Another possibility is simply to treat the thing for what it is—biology—decoupled from conceptualizations of computation and cognition. I think many fields of science did this throughout history: we did believe at some point that the sun rotated around us, and that the elements consisted of air, water, fire, and earth, because, well, it just made sense. Until it didn’t. I’m less optimistic about this, because it requires some kind of paradigm shift, which would typically be conjured up by somebody having a psychedelic mega-trip. Except in this case, one might fall deeper into introspection (as I am told by other people, of course) and come up with a brand new theory of sub-conscious representation. But still, I like to ponder on this thought: what does an understanding of “what the brain does” look like without representation?