It’s funny how life works sometimes. Last Friday, I got on campus just before noon like a good graduate student, and on my walk to the office, I saw one of our department admins standing behind a table with a stack of Subway sandwich boxes, right beside the door to a classroom into which people who collected the free lunch entered. Should I should carry on with what I’d planned to do, or sit through an hour long seminar with some free lunch? Turns out, the event was to celebrate Black History Month and honor the black scientists that have had tremendous impact with their research on the brain and cognition. I’d actually gotten emails for it a few days ago and thought it might be interesting, and now armed with the prospect of free food, it is an offer I cannot refuse. Turns out, it was one of the most illuminating experiences I’ve had at, and about, graduate school.

Our own Dr. Lara Rangel gave 20-minute talks about 3 prominent black scientists across the country: Todd Coleman, Carl Hart, and my favorite, Dr. (^2) Emery Brown. Her short exposition on his life and professional experiences were very well done, and one thing that stood out for me in particular was a snippet of this video she shared. It was an informal talk & Q&A session he gave at MIT where he talked about his career trajectory starting from he was in high school. The link starts the video at his answer to one of the questions, in which he summed up the experiences of medical and graduate school, sorta like a condensed version of the whole talk itself. But the whole thing, albeit long, is very worth checking out (if you’re really short on time and don’t believe me that he’s a super dope guy, go to 1:07:00).

So who is this guy? Just to keep it brief, for folks outside of the neuroscience community: Emery Brown is a clinician-scientist who is a practicing anesthesiologist and also studies the effect of anesthetics on the brain, using pretty sophisticated mathematical and computational tools. To me, he seemed like a guy who knew just about everything. In my limited experience, most clinician-scientists’ research geared more towards the clinical side, and less about mechanisms in a scientific sense. Not that that’s a bad thing, but it’s a framework that I can’t relate to as much. Emery Brown, though, felt to me more like a full-time computational scientist who just happened to be a doctor, and his appointments and accomplishments reflect that. This is a guy who, among many other prominent academics - like the Sejnowskis and the Buzsakis and the Eve Marders and the Geoff Hintons - you aspire to mimic some day.

So why was this short session illuminating? Well, academia, like medicine or law or business or professional sports or anything really, is an field with clear signposts of success, as well as being full of high-achieving people. Often times, we look to these prominent figures in the field AS markers for success, and we aim to emulate what they’ve done in order to achieve success as well. The problem is, though, that most of these people are well into their careers, often in their 50s or 60s. And when you look at the paths left behind by those who have summited peak after peak in their lives, it is simultaneously inspiring and defeating - how could I ever hope to get there? You see where I’m going with this. When a green-horned graduate student into their 3rd or 5th year of full-time science looks at someone 30 or 40 years senior to them, how could it feel like anything but an endless life of playing catch-up? And that is why I found the session (and the Youtube video) so enlightening: it told his story from beginning to end, specifically, when he was also just a medical and graduate student, and how quirky he was then.

Everyone has a story, starting from when they’re a baby to when they’re greying and brittle. In academia, we pluck out the success stories and invite them to talk about their scientific achievements and newest discoveries, but rarely about their personal journey wading through successes and failures - lots and lots of failures. When we do talk about someone when they were young, we pretty much only talk about the Einsteins and Newtons - Nobel-quality work at the tender age of 25. We rarely get to hear about how someone’s family and culture and social and economical background influenced how they got to where they are today. But those are the stories that are worth telling. Sure, they’re usually not glamorous at all, and that’s the point: most of our lives on the day to day are not glamorous, whether if you’re a medical student or graduate student, or a young professional in any industry.

I think the growth of science communication on social media where professionals can share their own stories, as well as being in a lab that encourages failures and personal lives, made me more tuned in to that than otherwise, and I like where it’s going. But in general, I think, for every scientific discovery worth disseminating, there is a personal story that’s just as, if not more, inspiring. I’m not saying this because I think we need to feel good about ourselves all the time and it should be all sunshine and no struggles, but exactly the opposite: your life, and everyone’s around you, is filled with ups and downs, twists and turns, diverging and converging interests, even if it is the life of a world-renowned anesthesiologist and brain scientist. Hearing those side quests makes us hopeful that our own side quests are also full of meaning - sometimes meaning yet to be discovered.

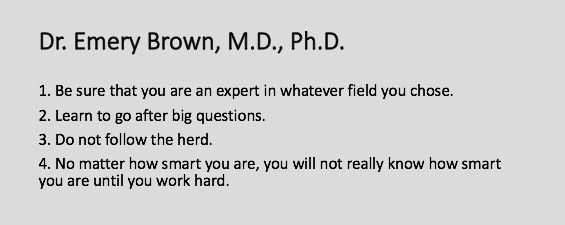

Finally, he had some parting advice specifically for Lara’s presentation to us, which I’ve taken the liberty to share (directly from her slides):