This is Part 3 (of 3) of the blog series on neuronal timescales, you can find here Part 1 and Part 2. There’s finally some useful stuff in this one, I think, as well as some strong opinions on scientific publishing (constructive and…ranty).

10. tenured professor runs own analysis…(October 2019)

…and graduate student proceeds to almost break it.

Part 2 got to the end of Christmas 2019. For this final story, I have to rewind a little bit, back to late October of 2019. This is right around SfN2019 in Chicago, and I gave a poster presentation on all the new results so far, including the anatomy and gene expression correlates. It went really well, and it was the last SfN as graduate students for the rest of the original cohort in the lab (but the first time shotgunning a beer for some). Right around then, we were starting to think about writing this work up and publishing it, reasonably confident that it would be quick (it was not) and that I’d be graduating soon (I did not).

For a paper like this to be meaningful, at the end of the day, you need to show some kind of behavioral relevance, otherwise “it’s just a methods paper”. This is especially true if most of the results, while cool, was recapitulating existing knowledge from non-human work. So we got to brainstorming. I say “we”, but in this particular case, it was actually just Brad, and I didn’t have much to do with prototyping this idea until we were ready to QA/refine the code and make the figures (though I almost broke the analyses a few times). I have two very vivid memories that summarize how this happened, and both had the flavor of “I thought tenured professors didn’t run their own analyses anymore.”

Moment 1: I’m sitting in lab minding my own business, as one does pre-pandemic, probably making my SfN poster. Brad comes in and goes “yoooo check this out”. We had talked about trying to show some behavioral relevance already, but apparently he couldn’t bear waiting for me to start digging around, so he went and did it himself. Obviously we weren’t going to run our own experiment at this point of the project (and given the historical precedent, or the lackthereof), so he found a human ECoG dataset collected during a working memory task that a friend from Bob Knight’s lab had deposited on CRCNS (the other patron saint of my PhD). This is vivid in my mind because we were sitting at the round kitchen table in the lab, and Brad described the experiment to me, and asked whether I think timescale would increase or decrease during working memory maintenance…

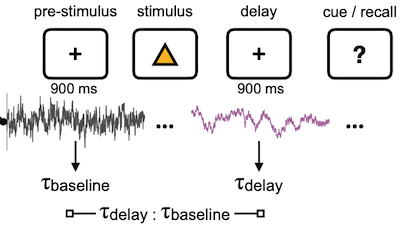

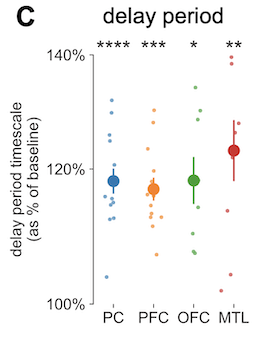

The structure of the task was standard as far as working memory experiments go: there’s a pre-stimulus baseline period, then a set of visual stimuli comes on the screen, then a blank delay period, then a cue for context-dependent recall response. In this case, there’s a pretty straightforward hypothesis: if working memory is the active maintenance of information, then it would be reasonable to expect the neural activity in those involved regions to have “more history”, or longer timescale. It’s a rather naive guess, but I went with it and said “increase”, and he had this dramatic slow-roll with a suppressed smugness on his face: it actually turned out to be true! We scrolled through dataframes in a Jupyter notebook and he called up the pre vs. post t-test statistics, and yup, there it was. During the delay period (holding onto information), timescale in all the recorded regions saw an increase relative to baseline (obviously the nice figure here was my doing, tyvm).

I was swelling with pride—my associate professor of an advisor is ready to become a PhD student again. But seriously, it was really weird and really fun to have that role reversal.

Moment 2: before the pandemic, Eric and I got into a nice habit of going to this bar in San Diego for house music on Wednesday nights (RIP Blonde). On one such Wednesday, we were at said bar and I’m shuffling my feet, and I get a Slack message from Brad:

Note the timestamp (it was actually 11PM PST, so not quite as bad as it looks…for both of us). This was apparently 2 days after Moment 1 above (and 2 days before flying out to Chicago), where I said I was going to check over his code, and I obviously hadn’t looked at it in the ensuing 48 hours. I don’t want to make it seem here like Brad’s always on my ass after work hours, because he never is. I’m usually the one sending random messages in the dead of night because that’s when I work sometimes. But here we are on a Freaky Friday Wednesday, and I remember this SO vividly because I’m now standing in the middle of this tiny crowded dance floor staring at my phone aka highschool-me. Alright, my interest is piqued, shoot:

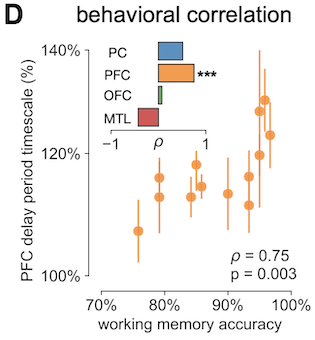

So what he had done was, beyond looking at within-individual timescale changes from pre- to post-delay period, he looked for across-individual trends. Specifically, was there a relationship between a person’s modulation of timescale and their average performance on this working memory task? This would be kind of crazy cool even without making any causal claims, because it’s a direct correlate of behavioral outcome (though I have lots of rants about this anyway). And yeah, consider my mind blown, because it turned out, across the 15 or so people in the dataset, the better their average performance was (x-axis), the more (longer) their timescale increased from pre- to post-delay (y-axis), and this effect was only significant for PFC.

Going all the way back to the radioactive decay analogy: the more volatile (shorter timescale) the element was, the faster all of it disappears, and the less useful it would be for reconstructing events farther back in history. Except, in the case of brain activity, we are apparently able to modulate the timescale of our neural activity based on behavioral demands, and the longer the modulation, the better performance one got (or vice versa, not sure), at least in this very simple task. There are lots of caveats and open questions here, especially in the causal direction of the modulation (is it brain modulating behavior, or behavior modulating brain, and where do neuromodulators come in?)

These were precious moments, from which came the core of the final analysis in the paper (Figure 4A-D). Of course, the “checking it twice” part of making a list again took way longer than making the list itself. In this particular case, I inherited the notebooks, refactored, broke the analysis, fixed it, broke it some more, fixed it some more, ran it through the gauntlet of tests until we were both reasonably confident that the result was not a fluke. These next two snippets of messages perfectly capture this sentiment, and as a whole, the project (and really, science).

11. the wrap-up (early 2020)

…yeah, so it did not take two weeks from then to finish the paper. But this wasn’t due to anything extraordinarily frustrating or stupid, it was just plain academic optimism and the inability to estimate time into the future. I had presented this complete set of results (including the behavioral stuff above) a few times, including to my PhD committee in my pre-defense meeting in January 2020. We collected all the feedback, prioritized the most damning criticisms, and did some extra work to address them. Protip: obviously, comments and feedback from trusted advisors almost always improve the project. But there’s an additional art to getting your paper trashed preemptively, so that you can address those shortcomings before the first round of reviewers have an opportunity to trash it harder. This saves time and emotional turmoil for everybody.

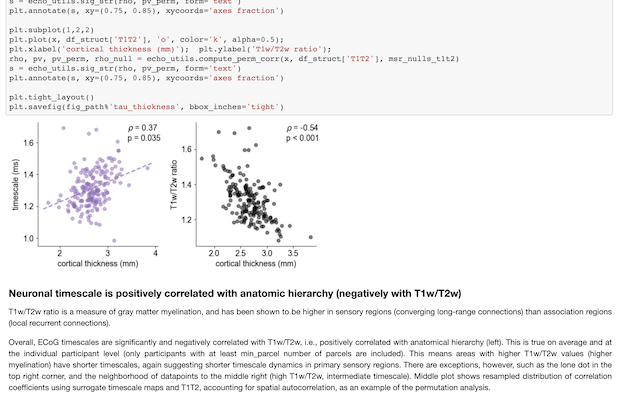

In this case, there were concerns over the validity of the correlations between the cortical timescales and the T1T2 and gene expression maps. I did a couple of things to mitigate that, including the gene ontology analysis, as well as redoing everything with the addition of regressing out the T1T2 map from both the timescale and the gene maps, then correlating their residuals as a way of asking “which genes relate to timescales above and beyond what’s expected from this primary anatomical hierarchy?” Just like the previous sentence, none of this is terribly…sexy, let’s say, in the context of the main results, i.e., finding the correlations in the first place. But I think I’ve realized in the course of my PhD that, almost always, the time consuming part is not the first result itself, but the checking and rechecking everywhichway afterwards.

Or maybe it’s not, maybe the endless thirst in finding out the answer for that very first time makes time itself feel like it’s running faster, and everything afterwards just feels like a big fucking drag. Alas, that’s science today: gone are the days where you can cook something up and send in a 2-page Nature Letter, literally like a correspondence to your bud. But I suppose that’s a good thing, and makes for better science. Plus, we have computers, Google, and open source data and software packages, like scipy, pandas, NAPP, and packages like brainsmash and brainspace for more sophisticated spatial correlation analysis, which were a timely god-send. Can you imagine trying to code this thing up by myself for this project? It’d be a primo hackjob. All these things make my life infinitely easier as a scientist, and none of this would be possible without them. This really made me appreciate how much foresight the people that started these various large-scale efforts had (like HCP, the Allen Institute, and CRCNS), as well as the open source software development communities. I don’t know how well I’ll keep to my words here (because laziness), but reflecting on this right now makes me genuinely want to not write shit code-not from a perspective of “that’s obviously the right thing to do”, but from a deep place of appreciation inside my heart, because maybe one day someone else would find a few lines I wrote useful.

12. and then time stood still + a rant and protip (March 1-March 124310798, 2020)

Judging by how things were going, 2020 was going to be great! All the main results were consolidated, and even though it took longer than we had thought, the paper was going to be finished soon. I had planned a short 3-months visit to Jakob’s lab (then in Munich) for April - June, so I worked quite a bit in that first quarter of 2020 to wrap up this paper before I left San Diego. Obviously, neither of those things materialized, and we all know what came next…

I suppose I was able to take advantage of the stay-at-home order, especially when California was first taking the pandemic seriously. I even got to see (and surf!!!) the fabled Blue Tide because I wasn’t able to leave San Diego. But it’s been 329487 days since pick-up basketball, and there was even a month of surf ban, so what was I to do except hole up in my apartment and write? Two months went by with the snap of a finger, I lost track of day and night—quite literally, actually, because on top of intermittent fasting, I tried biphasic sleeping for a few weeks (lol). I also tried making cold brew with wine. It was…disappointing. Look, this is the kind of weird shit a graduate student who lives by himself and can’t go outside ends up doing, at least I didn’t start drinking soylent again…yeah I mean at this point in the story, there’s nothing exciting really happening anymore, so I guess I will write something that may be of use to you, my loyal readers:

Even though the paper took a solid extra few months than anticipated to finish, it could’ve taken much longer. The reason that it didn’t is because I didn’t actually have to write much—most of the results and methods were already written. My current workflow, roughly, is to run heavy-duty/slow analyses in python scripts, and save out the intermediate results to disk (in whatever format). All the final-stage computations are then performed in Jupyter notebooks, including collecting the intermediate results into pandas dataframes, doing statistics, and making figures. In doing this, I’ve gotten into a habit of writing long-form paragraphs describing the code and the subsequent results in the markdown cells in the notebooks themselves. Some of these even come with a “background” section, with some relevant literature referenced within, so that each notebook itself is almost a mini-paper on that set of results (see the working memory results, for example).

I definitely didn’t come up with this, nor do I do it the best. Many, many people before me have talked about the notebook as the final scientific product, and you can even include fancy things like widgets to play with analysis parameters. I also didn’t do this thinking that this would eventually be useful for writing the final paper, not at all. I did this because I fucking hate journal articles in its current form. I really, really do. We’re in the 20th century now, there’s electronic media and embedded hyperlinks, and even embedded executable code. There’s absolutely no reason to still hold onto pretend-paper as the de facto medium of scientific communication. This has been literally the same medium since the 1700s, except now we pay even more money for less physical material. Where’s the lie fam?

I get it, some people prefer paper, and even go as far as printing articles out. I am one of those people when I have a printer, and I love physical books. But the pdf is the least worst of all current solutions, not the optimal, and we’re talking about what’s potentially an entirely different conceptualization of the scientific process, at least for computation-heavy fields. If all of us use code, data, and marinade those two things together to create results anyway, why go the extra step of producing a 10-page text document elsewhere? Why not just write directly where the code is created? Yeah, maybe nobody wants to read a “paper” in C++ comments, but now we have things like markdown and Jupyter, where you can quite literally explain things in the thick of the action and look pretty doing it. So why not do that? If I had it my way, this set of notebooks would be what I submit to “journals”, or whatever peer review mechanism independent of the accreditation party is. That’s why I wrote the whole thing in the notebooks, and thats why I truly love eLife as a journal (more on that later).

Anywayy, thank you for coming to my TEDTalk, hopefully you’ll consider doing this too now, and one day, we can all start passing runable research notebooks as the scientific output, instead of saving pdf links that will never be opened again. But if you’re not convinced, here’s a very tangible benefit: instead of undertaking this massive paper-writing task in one go after all the results are finalized, writing up the methods and results in real-time as you finalize the stats and figures automatically chunks the work into intuitive pieces. Affordances! This is a protip even if you don’t write them in markdown in the notebooks, for whatever reason (you’re wrong). Just write them down somewhere—Google Doc, Evernote, whatever—and be as verbose as you can as you produce each result. Write as you go. In the end, just copy and paste the stuff you’d already written, wholesale, and do some light editting, and that’s a paper!

That’s how I spent my first two months in quarantine. The preprint was up on bioRxiv the last week of May, we sent it off to Nature, George Floyd was murdered on camera, and I packed my car and went into the desert for a week by myself.

13. I love eLife

Yes, after all the hemming and hawing about dropping outdated traditions, we submitted to Nature—sue me for conforming to the current bar for getting an academic job. Mans gotta eat. In any case, I won’t speak to how the rest of the guys felt and just share my own opinion: it’s not so much that I thought the paper was “good”, whatever that means, to pass the bar at Nature, because I know we’ve all gotten salty about somebody else’s work (“undeservingly”) published in Nature. It’s more so that I thought it ticked all the boxes for flashiness, especially with the wide range of data and methods we used, and for human neuroscience! To be more self-deprecating, it was the right kind of marketable garbage with broad appeal, or so I thought. It was eventually a editor-reject after two weeks, because it “lacked impact”. But it is what it is, can’t be mad, and I was in the desert for the first of those two weeks so I got my kumbaya under me.

I’ve already had my one rant per post, so I want to talk about something positive instead. Somebody told me a joke once that PNAS stood for “Post Nature And Science”. People are not going to stop sending to Nature and Science, for obvious reasons. But I think we should strongly consider eLife as the new “PNAS”. I’ve now served as both reviewer and author at eLife, and I’ve had overwhelmingly positive experiences both times. To summarize succinctly, I feel like I’m treated like a human being, living in the 2020s, and interacting with other human beings at their office, instead of typing into an electronic void that serves solely as the interface between authors and reviewers. No offense to editors/administrators at other journals, if you also make it a point to be human—you have my thanks.

First, eLife takes submissions directly from preprint servers (like bioRxiv), and they recently announced that they will start to only review preprints. Granted, there was still some extra stuff to be done and forms to be filled out in the process of formally submitting, but it’s definitely a move in the right direction. On top of that, if you so choose (as an author), the “raw reviews” you receive are posted back on biorxiv itself, so people can see each reviewer’s responses to the original version of the article. This is valuable in many ways, the most important of which is the transparency provided into the review process. So much of the “scientific progress” actually comes in the form of ideating and negotiating during the reviews. As much as I hate to admit it, more often than not, the set of comments from 3-5 expert reviewers make the original work better, and even contain genuinely novel insights sometimes, so it’s a shame for those comments to never reach the light of day. At the very least, posting it publicly also clearly demonstrates if and when a single reviewer is being unreasonably obtuse.

Perhaps my favorite thing about reviews at eLife is that, first, after all the reviewers have submitted their comments, there is a round of “consultation” for the reviewers and editor to hash out any disagreements outright, before it reaches the authors. The editor reads and digests all the reviewers comments, and then organizes them into a single structured document, as opposed to 4 people’s separate notes. This task can range from distilling and re-interpretting all the reviewers’ points into a summary, to just moving around the comments into shared thematic categories, and anything in between. If this doesn’t seem like a big deal to you, consider yourself lucky, because dealing with 4 disparate sets of (repetitive and/or conflicting) comments is a gigantic pain in the ass. As a reviewer, I always check the other reviewers’ comments because often it’s relieving to see that all of them share similar sentiments on a particular point, and that I didn’t say anything incredibly stupid in hindsight. This now happens in the consultation. Also, every author and every editor has to do this internal collating anyway (at least I hope so), so why not just save the authors some time and effort, and send out those notes as a distilled guideline?

This whole process acts as a quality assurance step for the reviews, and also explicitly sets the revision priority for the authors, which is extremely valuable for all parties involved. Finally, when the reviews reach the author (me), all I have to do is to go through the document one bullet point after another, more or less confident that the comments are internally consistent. Finally, if the paper is fortunate enough to be accepted after revision (encouraged to be limited to a single round), the reviews and responses are published as a part of the article itself. Again, maximum transparency, and this begins to truly feel like a productive scientific discussion, instead of an adversarial combat of who can write the most words so the other parties become disinterested enough to stop arguing. Please, journals (and editors), take some responsibility as the middle person in this process, let me know that you are alive and have important opinions, and not just dump the task of placating the whims of the reviewers on the authors. If you are an eLife editor reading this, you can always count on me to review for you, 100% (but timeliness not guaranteed).

Lastly, and relating to my earlier point on being not in the stone age of academia anymore, eLife has launched in 2020 an effort called Executable Research Article (ERA), which is basically live runnable code embedded in the online version of the article. “Whaaat? No way!”. YES. F-ING. WAY. ALL THE WAY. In this format, you can click open a figure, and change the code on the spot to see how it affects the resulting visualization. I was so quick to volunteer for this thing after our paper was formally accepted that the ERA team told me I actually had to wait till the nice typeset version is live on their website first, which took about a month. So I actually just started this process yesterday, which, as far as I understand, involves me copy and pasting over code from my Jupyter notebooks and link to the correct spots in the paper, in between the relevant texts—basically, a literal fucking reproduction of what my notebooks already are. By the amount of profanity littered in this paragraph, you can tell I’m emotional—I’m not angry, I’m ecstatic. This is my dream come true. Obviously I’d be happier if we could’ve just started from my notebooks in the first place, 6 months ago, but that’s not on eLife. Funny enough, as I was reading through the ERA guide yesterday, there was this gem of a blurb right at the beginning:

This is now my scientific side-quest: to see the day when eLife goes from PostNatureAndScience to BeforeNatureAndScience.

14. final thoughts on reproducible luck

And that’s a wrap! The reviews did take some time to get back, but in the end, these were the most positive and constructive set of comments I’ve ever gotten in my life for a journal article, and it was accepted shortly before I defended my PhD, so I’m really counting my blessings. If you followed this story all the way through, you should see —as I had alluded to many times—that this project was the result of many fortuitous encounters. Not only was I lucky to meet the right people at the right time, I was lucky to be in those situations in the first place, which means having the privilege to be advised by a “Second rate” neuroscientist (his words) at a first rate institution, and thus having the resources and good name to take advantage of those opportunities. I recognize all of that, that’s what luck is: being able to capitalize on fortuitous opportunities.

Unfortunately, I can’t teach luck, and I can’t (yet) provide any real opportunities. I also don’t necessarily recommend stumbling around haphazardly like I did here, it’s hard to reproduce. So what can I recommend?

Well, basically all that one could do to be prepared when presented with such opportunities. One of the concrete things I’d recommended above already: if you already use Jupyter notebooks, treat it like the entirety of your project—code, data, and paper. Of course, that only applies to semi-mature results and ideas. But with that in hand, I found that it was much more efficient to send people early results in the form of a GitHub link, instead of rewriting long emails or reports, especially to people you’ve only just met at a conference or in passing.

Another thing, and this is not necessarily a recommendation, more so a note on what worked for me: read lots but at the right time. What does this mean? I think this really only applies to computational/theoretical work, but before I have a good concrete idea, I read relatively broadly, meaning all kinds of random shit from whatever subfield of neuroscience, and whatever I see on Twitter. This breadth gives me inspiration for ideas and connections between unrelated things. Once I think I have a good enough idea, I stop reading. This is partly because I’m absorbed in actually screwing around with code so I don’t have time to read, but it has a very tangible benefit: usually, the more I read, the more I convince myself that something’s already been done, and the more pointless my idea seems (and never the opposite). I don’t think this is untrue, because nothing is really new under the sun. But nothing is exactly the same either, and often it’s only because you have a unique perspective into the connections already that it feels like old news, but you may be the first and only one that sees that.

Sometimes the only reason for pursuing vs. abandoning the idea is actually thanks to the sunk cost fallacy: the more I’ve already done, the more I’m invested in making it an actual thing, even if it’s not particularly groundbreaking. But if I’m convinced that the idea is nothing new before I have a single result, I wouldn’t even bother to start. Again, it’s almost never identical, and there is so much we don’t know. Even if two people try to implement the exact same idea, they might end up having their own unique points. Then, when the time comes to place those results in the context of the existing literature, I obviously try to read as much of the relevant literature as possible, or, at the least, I try to collect them, to make sure I’m truly not reinventing an identical wheel. At that point, it’s a matter of crafting the research niche after the fact, which often looks different from the real story (i.e., this one). This is why I say to read at the right time. Not sure how this applies to experimental work where you need to be relatively certain of all the existing work before investing in running an experiment, and obviously this already assumes some level of technical competency while only lacking in inspiration, so better suited for year 3+ PhDs.

Last point, and this is more of an advice for myself than anyone, because I think I’m not great at this still: talk to people. There is almost zero cost (or risk) in talking to someone about my research, and only benefits to be reaped in case of potential collaboration, or at the very least, a fresh set of ears and eyes for ideas. I know all this, and I (clearly) have no issues in writing about my stuff, but I just can’t bring myself up to talk about my research, especially at a conference. I feel like I still don’t have a good elevator pitch, and also I get tired of the “what do you work on? who do you work with?” exchange after the 10th time in the same day. I’d much rather talk about something completely non-sequitor, like dinosaurs, and see where that leads us as human beings. Whatever the method may be, the point is, at some point, social capital (i.e., people) becomes the most effective way of amplifying your value for the world, though probably only if you enjoy their company in the first place.