There’s a pretty famous anecdote in the sales world that’s now immortalized in a scene in the Wolf of Wall Street. I don’t know if the real Jordan Belfort came up with it, but it goes something like this:

There’s a pretty famous anecdote in the sales world that’s now immortalized in a scene in the Wolf of Wall Street. I don’t know if the real Jordan Belfort came up with it, but it goes something like this:

JB: sell me this pen.

Schmuck #1: um…well, it’s a great pen, it’s for professionals…

to the next person

JB: Sell me this pen.

Schmuck #2: um…this pen works, it’s dipped in gold for a luxurious feel…

JB: (oh ffs…)

Those are perfectly true statements, and they describe something that everyone can see. It’s a natural thing to do: we gravitate towards describing and therefore selling what we believe to be highlights of a thing. But unless you’re selling to somebody who likes buying stuff they don’t need (another schmuck, perhaps), this usually doesn’t work.

How do you sell this pen then?

Short answer: you don’t sell the pen, you sell a problem that requires the pen to solve, and you make your buyer feel like a genius for figuring out that they need to buy a pen from you.

That sounds like common sense, but I’ve only recently learned to apply, and more importantly, to enjoy that component of my own job: selling my research. I’m currently in the middle of a pretty interesting part of a very interesting project. This past week, Brad and I have been trying to write the abstract and introduction for this latest paper. We’ve been trying to find the right framing for it for the last month or so, for a project that genuinely surprised the shit out of me at every stage, every time I saw the results of an analysis. More times than not throughout this project, I would literally say to myself, “well shit, this is a minor miracle that it worked.”

Over the last two months, though, I’ve given a handful of informal talks on this project to people from a variety of fields, and one of the most consistent responses I’ve gotten is “wow this is really cool…but so what? Did we not expect this to happen?” The coolness was felt. The significance? Not so much. But these are people whose feedback I respect, so I began to ponder a little more deeply about why it’s so unsatisfactory for them, and what is the gap between what I see and what they see. Thinking about that response transitioned into the writing problem I have in front of me now, which is to translate “look at this, this is really cool” to “this science solves a very concrete problem and you should read/publish/think about this right now”.

A word of warning here: I’m (obviously) still in the process of doing what I’m about to tell you, with no success guaranteed. So take this not as a recipe, or even a guide, but an entertaining reflection. If it makes sense to you, use it, adapt it, improve on it. If not, tell me how you would do it instead, because I need to know (to finish this paper).

Selling The Holy Grail

Right up to this point in graduate school, I’ve had a minor disdain for “selling” my work. I understand why that need exists, and I try to work on it because of that. But I didn’t like it, and I didn’t think it was a part of the actual scientific work, and that it’s somehow a little…“dirty”. I think most scientists share this visceral reaction to the salesmanship component of doing research, especially budding graduate students, mostly because it’s hard. All this made it very surprising that I’ve really enjoyed coming up with a “problem” to sell these last few weeks, and this is how my thought process and feelings have changed about it:

I’ve always conceptualized the science as being finished once the results were described, and the “selling” that comes afterwards is mostly advertising and making claims that are more general than I’m comfortable with, for the sake of subtly conveying without outright lying that “this study is more than what it is.” That’s what “selling” meant to me. I think my issue was that I never really truly thought about “why this work is significant, to who, and what it takes to convince someone of it”. It’s probably from a combination of 1) interpreting that question as more antagonistic than it’s meant to be, and 2) fearing that if I really thought too hard about it, I would be forced to conclude that it’s not significant or important at all. As a result, the salesmanship ends up a little half-hearted, and with every sales pitch comes an exasperated sigh in my head, “isn’t this obvious?”

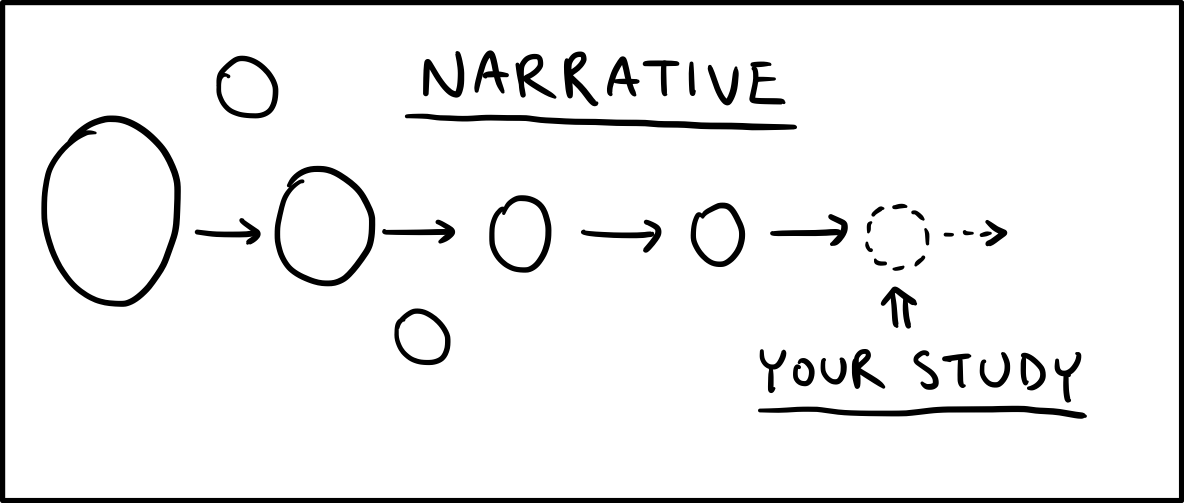

Why is this the case? If I were to venture a guess, I’d say it’s (largely) because of the very pervasive narrative we have about science, that at least I have internalized: that science is deductive and we make incremental progress. In other words, before conducting any experiments or analyses, we should have worked out a sequence of inferences piecing together facts from previous research studies, which leads us to our specific knowledge gap. With that in hand, the only logical conclusion is to conduct the set of experiments I will now conduct, to answer that specific question and fill the gap in our knowledge. It’s like paving a garden path one stone at a time - the next stone is a logical and obvious extension of the stone I’m standing on right now, one after the other. From this perspective, the research problem is (in some sense) “god-given”, it’s like asking what comes after the number 8, and it becomes completely unnecessary to make a pitch to sell it. Seeing how it’s god-given, I’m not even sure what can be said if you had the actual f-ing Holy Grail in your hands and tried to sell it.

The problem is, this narrative of logically deducing the next research gap to be filled before we fill it isn’t quite true. Reflecting on my own experiences, that’s definitely not how things happened for me (or anyone I know), and I’m pretty convinced that that’s also not true in general, at least of neuroscience, because that doesn’t actually make any sense.

Many Roads to Rome, Mine Are More Meandering

I’ll first tell you why it’s not the case for me, and it’s simple: I literally have never gone through that process of deductive reasoning a priori because almost all my work resulted from me bumbling around trying shit I thought would be interesting. I am, of course, aware of the general problem I’m working on, and why that high-level gap should be addressed. When it comes down to the specifics of the study, the only real important thing to know is that no one has done quite the same thing in that exact way before. It’s certainly true that within the context of a single project, follow-up experiments arise as a product of deductive reasoning based on results from previous experiments. But outside of that, everything between the vague high-level awareness to the concrete research project itself remains unknown until the very end, when I’ve compiled most of the results. Only at that point comes the exercise of really diving into previous literature to piece together a specific knowledge gap, or as I like to call it, “manufacturing a problem”.

That’s what I’ve been going through the last few weeks. I know these particular results don’t yet exist in the literature based on my own (sometimes limited) readings. It’s also corroborated by other experts in this specific field when I’ve presented at conferences (even though novel maketh not significant). So now I have this really interesting challenge of constructing a research gap after the research has been done (and it has to be a little substantive than “no one has done this yet”), which completely goes against that previous notion of following the stones one at a time and laying them into the spot they were meant to be on.

At this point you might say, “well Richard, that’s just because you are a terrible scientist. If you were worth your salt, you would’ve have done your homework before conducting your research, laying out the sequence of relevant studies and deducing the proper experiments that address existing knowledge gaps in the field. Also read more, period. And work more. Also wake up earlier, etc. etc.” You might be right, I will entertain that someone more diligent and organized may have worked out that chain of reasoning a priori. I think this is also something that comes naturally with experience, meaning simply existing and breathing the research for longer, such that someone later in their career may know the field so broadly and intimately that they have a grasp of the precise experiments that are needed to advance our understanding in those directions. I will even concede that if you do this exercise beforehand, it will probably save you a bunch of time from doing useless research.

Well, I prefer bumbling around, and to each their own. But more importantly, I argue that whether you lay out that logic before or after you do your research is irrelevant in the most important dimension (assuming that you have at least a vague awareness of where the current state of knowledge is at).

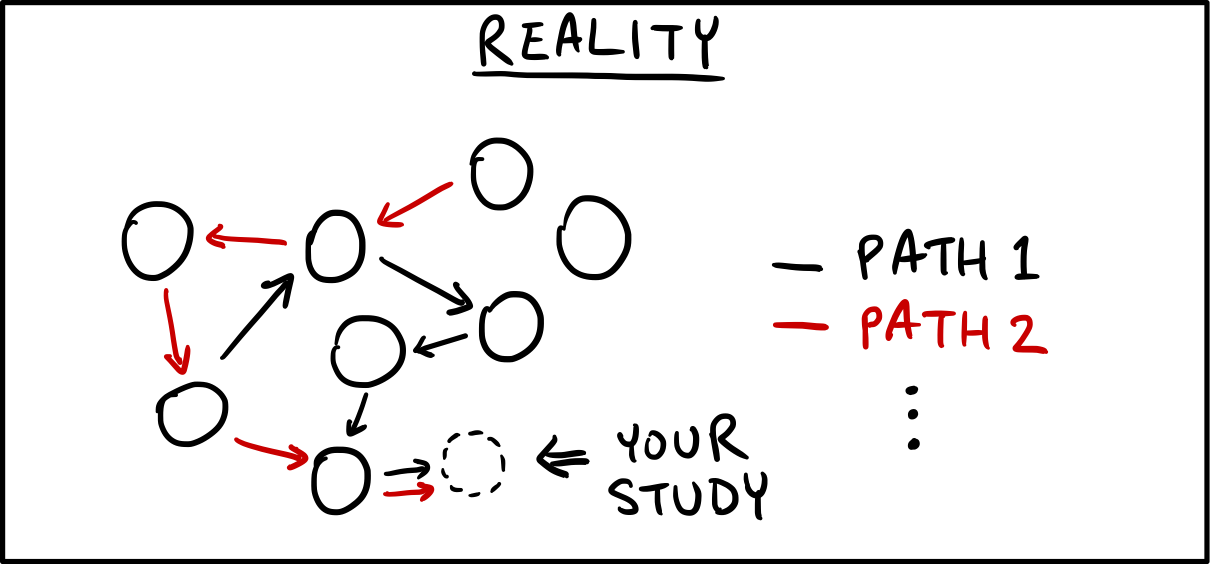

The truth of the matter is that, the notion of a natural sequence of deductions leading to exactly why a piece of work should be done is simply a fantasy. In reality, the process of manufacturing a knowledge gap is as much of a creative process as it is a deductive process, because there is not one path that could be paved, whether you do that before or after you conduct your own research. In other words, you don’t get the problem for free, you have to create it. Also, if you’ve ever finished a research project, you know that it digs up more questions than it answers, so it’s really a divergent process, which means that unless questions arising from different studies collide, it’s basically impossible to have just a single converging sequence of deductions. Perhaps a better imagery is that of stones scattered all around you, and there are near-infinite number of possible paths you could construct by drawing links between some subset of them, all of which equally logical and valid from a knowledge-building perspective.

Some of those paths may be more efficient than others at bringing you to some fruitful destination, such as a complete understanding of the human brain. But as of right now, neuroscience is a bunch of stones scattered around a garden, because we know so little, and there is so much uncertainty surrounding even which direction is good, nevermind which sequence of stones. Maybe it’s different in physics, where we’re fairly sure we’re looking for dark matter or the Higgs Boson.

But with this uncertainty comes a tremendous sense of opportunity. This is true at the highest level, since you can bring in knowledge from many other related and unrelated disciplines, like complex systems, statistical physics, machine learning, etc., like you’re importing other colorful stone path templates from someone else’s garden. It’s also true at the lower level, where I can build a sequence of logical deductions from a number of previous studies, all of them logically sound and factual, but some of them more appealing (say, to an editor). It’s this process that I’m really surprised to identify only now as being a creative process, and even more surprised that I’m enjoying this otherwise “dirty” salesmanship problem.

The Paradox & the Solution

Before I get on with some “how-tos”, I just want to comment on how paradoxical this all is: earlier I said the notion that science is deductive a priori is a fantasy, but we know exactly why that fantasy exists. Read any paper. It will start with a general introduction catered to the level of expertise of that journal’s audience, and some sequence of facts laying out the things we do know. Inevitably, the heroic tale hits a wall (or a hole, whatever metaphor you prefer), where our knowledge ends, and more importantly, further knowledge is so absolutely and urgently needed. What comes next can only be described as divine intervention, or some really smart people doing really smart work, because lo and behold, the rest of the paper tells us exactly how that gap is filled.

I say that in a tongue in cheek manner not to be disparaging to literally every single scientist who’s ever written a paper that framed their research, but to bring to light an absurdity I’ve never thought about until right now: what about all the other equally plausible and rewarding gaps that are out there? Obviously a single research project can’t answer all of humanity’s questions about the brain, but is it at all surprising that this narrative is so pervasive given the way we are required to set up our stories as a Sherlock-esque game of deduction?

Well, it turns out, that narrative is also optimal for framing and presenting your research. Maybe it’s not a global optimum, but at least a local one, in the sense that it will get your paper published, though I think doing the exercise of laying out those sequences and deducing (or creating) the significance in a larger scientific context is absolutely valuable.

Creating a Research Space (CARS)

Man, let me tell you, it’s good to be good, but it’s better to be lucky. I had two meetings this week with Brad about how to build this narrative, on Monday and Wednesday, both ending in lots of head scratching and “let me think about this some more”. Okay, it just so happens that I’m a graduate writing consultant at the UCSD Writing Hub, where we help other graduate students on all kinds of academic and professional writing (that will be a whole other post). On Thursday, I get pulled to help a friend facilitate her workshop on, you guessed it, framing your research and writing introductions to your thesis! Turns out, there is a course at UCSD on writing your Master’s thesis, and the professor wanted some outside expertise (if you could call us that) on this exact topic. So Haley puts together a fantastic presentation and a workshop package on the CARS model (Creating A Research Space). As we’re doing our pre-workshop prep meeting, I read through the package, and I’m like, “holy shit, THIS. THIS ME. STRUGGLES. THIS ME RIGHT NOW.” Needless to say, I got a lot out of that workshop, and from the feedback we got, so did the students. I think what was really helpful for me was not just the content of the CARS model, which is a useful guideline to keep in mind while writing (and reading literature), it’s reconceptualizing this act of manufacturing a research gap as selling a problem, instead of selling a product.

I won’t go into depth on the CARS model here. If you’re at UCSD, go to her next workshop at the Writing Hub. Otherwise, read this. In brief, this framework presents an argumentation strategy for one’s introduction as 3 “rhetorical moves”:

- Establishing the territory: introduce the knowns and the significance of this general line of work, e.g., “neuropsychiatric disorder X is a debilitating disease that affects 2 million Americans, and we know it’s linked to A, B, C brain structures.” This is generally where you talk about all the previous relevant research, and not only listing them out, but structuring them sequentially in more and more specificity to arrive at…

- Establishing a niche: …here, which is the specific gap that is currently missing. A niche is a small hole. Mind blown. These niches can come in different flavors, such as a counterclaim (debating the validity of some existing evidence), or question-raising (“given what we know, it’s still unclear what the mechanism of X is at the cellular level”).

- Occupying the niche: hallelujah we done solved it (or at least got a little closer), and let me tell you all about it.

This right here is not only a template for framing one’s research, it’s straight out of the Jordan Belfort manual for selling. You’re not jumping directly to Move 3 to sell this useless but super cool pen. You have to go through Moves 1 and 2 to convince somebody that they have a problem. The subtle art here, and I think the main reason why this works, is that when you set up the problem, you don’t ever mention the pen. You build the problem just a little bit ahead of your reader, such that they can guess where you’re going before you go there. Do this for long enough, they will realize they need a pen before you tell them you happen to sell pens. I think this is true for writing in general, where you want your reader to follow your thought process, not your word process. As in, the thought that’s implied by the words they’re reading, not the literal words they’re reading as they’re reading them. Academics are smart people, if you build your narrative such that they naturally arrive at the same conclusion as you later introduce, they’ll probably think you’re pretty smart too.

Obviously, this is not set in stone, and implementing it still requires thought and practice. But I think what I like the most about this is the insight it granted me by calling these rhetorical strategies as “moves”. Again, the sequence of deduction is not a god-given and obvious chain of dominoes, but pieces of evidence that are cleverly chosen and structured. It requires creativity to pick out and piece together, all the while satisfying the constraint that they have to be true and logically sound from a scientific point of view, and that makes selling science special for me.

Who’s Buying?

Two last notes that I think are interesting and useful. First, and most importantly, you have to consider who you’re selling to. Nevermind the pen analogy, let’s just go to the science. Your paper gets read by four largely non-overlapping sets of people: the editor, the reviewers, rest of the scientists in your field, and the public (maybe). Those are laid out in order of decreasing importance for publishing your paper, but of increasing importance for writing clearly and concisely, and most importantly, truthfully.

Editor reads your abstract and “letter to the editor” once, decides to toss or send to reviewers in probably less than 15 minutes, 30 if you get lucky. They also happen to be the people that makes the final decision for publication. So you really want to make sure their needs as a buyer are met if you want to make the sale, but it’s probably not so important that they get the truth, the whole truth, and only the truth (because, let’s be real, they’re used to being fed bullshit). The reviewers have a different set of needs, which for the most part are 1) their relevant papers are cited and revered, and otherwise kept happy, and 2) your shit holds water - in that order. You can see how much faith I have in the scientific publishing process. The point is that if a reviewer for whatever reason doesn’t like you, your tone, your advisor, or your poster from 3 SfNs ago, they can and will find ways to banish you and your dumbass paper out of the living realm twice over, because nobody’s data is perfect and free of “plausible further experiments” that require 2 more graduate-student-years to run.

With those out of the way, I think the actual scientific community who reads and builds on your work, and the public (including the science journalists) who hears about your work on NPR or whatever, are the most important to get right for. They also don’t make editorial decisions, though 80% of them will inevitably read your paper and say, “really? This paper? Nature?” I don’t think I need to say much more about this.

The second note is more of a shower thought: the scientists that end up becoming really influential and have a long career are probably not the problem solvers, but problem sellers. If you kill the research programme you work on because you just went ahead and solved it, without providing some potential further works, you might be hailed as a genius, but nobody’s going to cite you, because they literally can’t even if they wanted to. You just put everybody that could possibly cite you out of their jobs. The people that end up becoming influencers (at least measured by citations) are the ones that put out data towards theories that are just plausible enough, but require many, many subsequent studies to further hone in on. Note here that plausible doesn’t mean “eventually right”. Actually, someone fairly experienced in all this gave me an advice last week for writing papers, which is to present a set of equally plausible hypotheses, of which one of them will eventually pan out and you hailed as a visionary. Not that that’s necessarily a bad thing, or even anyone’s intentions, it’s just a very counterintuitive observation.

Anyway, this is getting long enough. Main takeaway: manufacture and sell a problem, so buying your solution is the only obvious thing to do. Check back in two months to see what good this does me in practice.